Splinting is an important part of the trauma resuscitation process. No patient should leave your trauma resuscitation room without splinting of all major fractures. It reduces pain, bleeding, and soft tissue injury, and can keep a closed fracture from becoming an open one.

But what about imaging? Can’t the splint degrade x-rays and hamper interpretation of the fracture images? Especially those pre-formed aluminum ones with the holes in them? It’s metal, after all.

Some of my orthopedic colleagues insist that the splint be removed in the x-ray department before obtaining images. And who ends up doing it? The poor radiographic tech, who has no training in fracture immobilization and can’t provide additional pain control on their own.

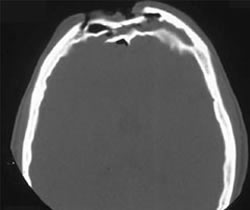

But does it really make a difference? Judge for yourself. Here are some knee images with one of these splints on:

Amazingly, this thin aluminum shows up only faintly. There is minimal impact on interpretation of the tibial plateau. And on the lateral view, the splint is well posterior to bones.

On the tib-fib above, the holes are a little distracting on the AP view, but still allow for good images to be obtained.

Bottom line: In general, splints should not be removed during the imaging process for acute trauma. For most fractures, the images obtained are more than adequate to define the injury and formulate a treatment plan. If the fracture pattern is complex, it may be helpful to temporarily remove it, but this should only be done by a physician who can ensure the fracture site is handled properly. In some cases, CT scan may be more helpful and does not require splint removal. And in all cases, the splint should also be replaced immediately at the end of the study.