As with adults a decade ago, the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in children is now on the rise. Whereas adult VTE occurs in more than 20% of adult trauma patients without appropriate prophylaxis, it is only about 1% in kids, but increasing. There was a big push in the early 2000′s to develop screening criteria and appropriate methods to prevent VTE. But since the incidence in children was so low, there was no impetus to do the same for children.

The group at OHSU in Portland worked with a number of other US trauma centers, and created some logistic regression equations based on a large dataset from the NTDB. The authors developed and tested 5 different models, each more complex than the last. They ultimately selected a model that provided the best fit with the fewest number of variables.

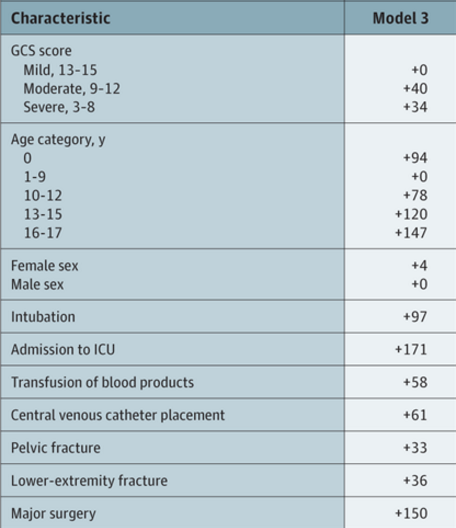

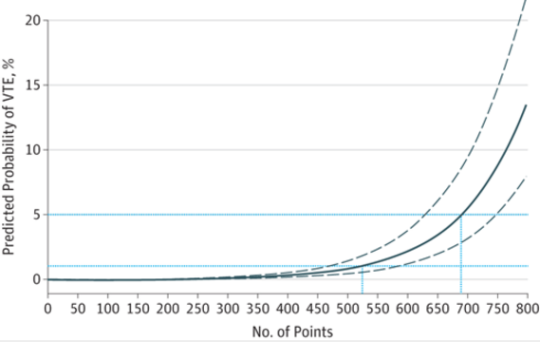

The tool consists of a list of risk factors, each with an assigned point value. The total point value is then identified on a chart of the regression equation, which shows the risk of VTE in percent.

Here are the factors:

Note that the highest risk factors are age >= 13, ICU admission, and major surgery.

And here is the regression chart:

Bottom line: This is a nice tool, and it’s time for some clinical validation. So now all we have to do is figure out how much risk is too much, and determine which prophylactic tools to use at what level. The key to making this clinically usable is to have a readily available “VTE Risk Calculator” available at your fingertips to do the grunt work. Hmm, maybe I’ll chat with the authors and help develop one!

Reference: A Clinical Tool for the Prediction of Venous Thromboembolism in Pediatric Trauma Patients. JAMA Surg 151(1):50-57, 2016.