In my last post, I described some of the telltale signs that could be seen in a trauma center’s TQIP report that might suggest there are issues with how they go about providing prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism for their patients. Today, I will analyze a systematic review and meta-analysis of a collection of research that compared the efficacy and safety of unfractionated heparin (UFH) to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) specifically for trauma patients.

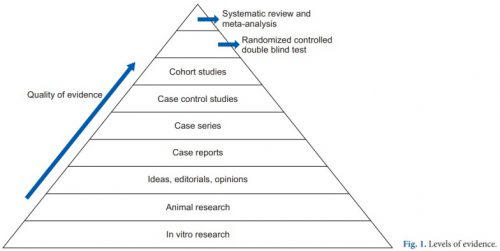

First, it’s important to understand the concept of research quality. There is a huge amount of research published these days, and it varies considerably in how well it is designed, executed, and analyzed. Here is a diagram that illustrates the levels of quality and the volume of research published at each level. By quality, I mean the applicability to clinical treatment of actual humans. For this reason, test tube and animal research are low on the pyramid.

The research that most people consider to be the “gold standard” (randomized, controlled, double blind) is very close to the top. There is one class that, if conducted properly, may even be better. That is the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Most people have heard of meta-analysis, and it can be very good by itself. This combines lots of smaller studies into one larger one. However, it may hampered by the quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis. The tenet of “garbage in equals garbage out” certainly holds. But a systematic review takes that one step further.

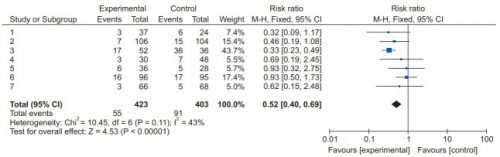

The systematic review compiles all possible studies related to a small set of research questions, and usually concentrates on the ones with the highest quality research design. The quality of each of the studies is evaluated, and a meta-analysis is then performed on the best. Results are usually represented in a forest plot. This is an easy way to illustrate the estimated results from a number of studies that address the same question. There is also an entry that shows the relative strength of all of the studies combined. Here’s an example:

There are seven studies included, and each is displayed with its risk ratio (RR) and confidence interval (CI). The final diamond is the combined RR and CI for the entire group of studies. In the example above, note that most of the studies have CI bars that extend over the risk ratio = 1 line, meaning they may not be significant. But when taken together, the final risk ratio of the group is well under 1.0 and does not cross over it, denoting significance.

Let’s now apply this concept to a group of studies comparing UFH and LMWH for prevention of VTE for trauma patients. Based on keyword search, the authors identified 1,227 records for screening. Of those, only 40 were tentativley found to directly address the question. After in-depth analysis, only 12 were eligible for final review. For various reasons, only about 1 in 100 papers could be used to try to analyze the question. This always shocks me.

Here are the efficacy results. All are statistically significant, and all but mortality were stated with moderate certainty. The mortality number had low certainty due to the fact there were only three studies and confidence intervals were very wide.

- Deep venous thrombosis: LMWH reduced by about 35% compared to UH

- Pulmonary embolism: LMWH reduced by 44% although certainty was low

- Any VTE: LMWH reduced by about 30%

- Mortality: LMWH reduced by 56% (low to very low certainty)

Safety was also analyzed, including bleeding events, unexpected return to OR, heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), and “any adverse events.” All of the Total Confidence Interval diamonds were situated on the risk ratio = 1 line, denoting no significant change when comparing LMWH vs UH. However, quality of this data was noted to be low due to the quality of the individual studies. This means that we do not really know the answer to the safety question with any certainty yet.

Bottom line: This is one of the best summaries of our research on UH vs LMHW to date. It broadly reviewed the available literature and found only a small subset to analyze. It is clear that LMWH is superior for prevention of DVT and VTE overall. However, the impact on pulmonary embolism and death is still unclear.

As far as safety, the studies are still of quality that is too low to use for a decent analysis. Although this study did not detect any increase in complications, we still can’t say with any degree of certainty.

So what does it all mean? We have been using LMWH for decades now. Most likely, if there were regular complications like bleeding, unexpected return to OR, or HIT we would have definitely noticed it by now. Fortunately, we only have a few anecdotes and case reports to scare us off.

Overall, there is good support for the use of LMWH exclusively in most trauma patients. However, the prescribing provider should always assess patient factors that may suggest that UH might be better is a specific case. But remember that using UH trades an unclear/unlikely safety advantage for a recognized decrease in efficacy.

Reference: Efficacy and safety of low molecular weight heparin versus unfractionated heparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism in trauma patients. Ann Surgery 275(1):19-28, 2022.