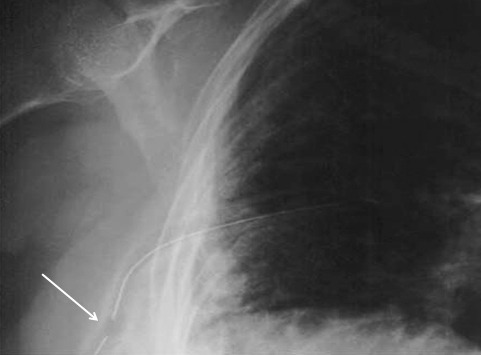

So you’re faced with a chest tube that “someone else” inserted, and the followup chest xray shows that the last drain hole is outside the chest. What to do?

Well, as I mentioned, there is very little written on this topic, just dogma. So here are some practical tips on avoiding or fixing this problem:

- Don’t let it happen to you! When inserting the tube, make sure that it’s done right! I don’t recommend making large skin incisions just to inspect your work. Most tubes can be inserted through a 2cm incision, but you can’t see into the depths of the wound. There are two tricks:

- In adults with a reasonable BMI, the last hole is in when the tube markings show 12cm (bigger people need bigger numbers, though)

- After insertion, get into the habit of running a finger down the radiopaque stripe on the tube all the way to the chest wall. If you don’t feel a hole (which is punched through the stripe), this will confirm that the it is inside, and that the tube actually goes into the chest. You may laugh, but I’ve seen them placed under the scapula. This even looks normal on chest xray!

- Patient with a high BMI may not need anything done. The soft tissue will probably keep the hole occluded. If there is no air leak, just watch it.

- If the tube was just put in and the wound has just been prepped and dressed, and the hole is barely outside the rib line, you might consider repositioning it a centimeter or two. Infection is a real concern, so if in doubt, go to the next step.

- Replace the tube, using a new site. Yes, it’s a nuisance and requires more anesthetic and possibly sedation, but it’s better than treating an empyema in a few days.

Related posts: