Yesterday, I went over the rationale for developing a practice guideline for something as simple and lowly as chest tube management. Today, I’m posting the details of the guideline that’t been in use at my hospital for the past 15 years. I’ve updated it to reflect two lessons learned from actually using it.

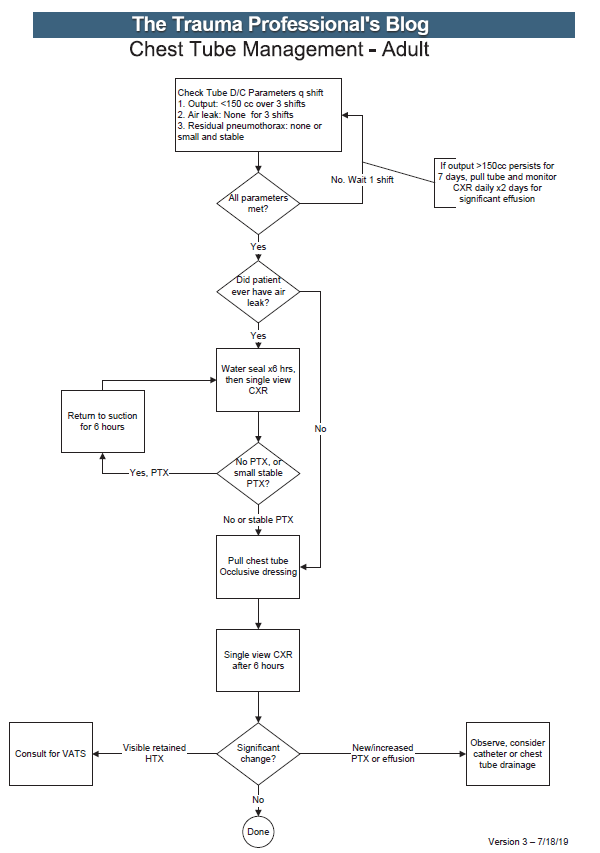

Here’s an image of the practice guideline. Click to open a full-size copy in a new window:

Here are some key points:

- Note the decision tree format. This eliminates uncertainty so that the clinician can stick to the script. There are no hedge words like “consider” used. Just real verbs.

- We found that hospital length of stay improved when we changed the three parameters from daily monitoring to three consecutive shifts. We are prepared to pull the tube on any shift, not just during the day time. And it also allows this part of the guideline to be nursing driven. They remind the surgeons that criteria are met so we can immediately remove the tube.

- Water seal is only used if there was an air leak at some point. This allows us to detect a slow ongoing leak that may not be present during our brief inspection of the system on rounds.

- The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma expects trauma centers to monitor compliance with at least some of their guidelines. This one makes it easy for a PI nurse or other personnel to do so.

- The first of the “new” parts of this guideline is: putting a 7 day cap on failure due to tube output greater than 150cc per three shifts. At that point, the infectious risks of keeping a tube in begin to outweigh its efficacy. Typically, a small effusion may appear the day following removal, then resolves shortly.

- The second “new” part is moving to VATS early if it is clear that there is visible hemothorax that is not being drained by the system. Some centers may want to try irrigation or lytics, but the data for this is not great. I’ll republish my posts on this over the next two days.

Click here to download a copy of this practice guideline for adults.

Click here to download the pediatric chest tube practice guideline.