I’ve been somewhat old school when it comes to chest tubes. Unlike some, I don’t believe that you have any control of where a chest tube goes if you are placing it in a closed chest. Only in the OR with an open one. And I’ve got plenty of x-rays to prove it.

And I used to think that chest tube size mattered when dealing with hemothorax. In theory, you need a big tube to get clots out, right?

Well, maybe not! The trauma group at the University of Arizona Tucson has previously done work on using 14 French pigtail catheters in lieu of a full-size tube. They will be presenting their extended experience with this concept at EAST 2017.

They have maintained a prospectively collected database of information on trauma patients with chest tubes for many years. This study focused only on those who had blood in their chest, either hemothorax (HTX) or hemopneumothorax (HPTX). They also looked at trends in their selection of chest drain tubes.

Here are the factoids:

- Nearly 500 patients were treated with a tube for HTX or HPTX during the 7 year study period, 2/3 with a chest tube and 1/3 with a pigtail

- Pigtails had more fluid drain initially (430cc vs 300cc, significant), and 1 less treatment day (4 vs 5, also significant)

- Failure rate and insertion-related complications were the same (about 22% and 6%, respectively)

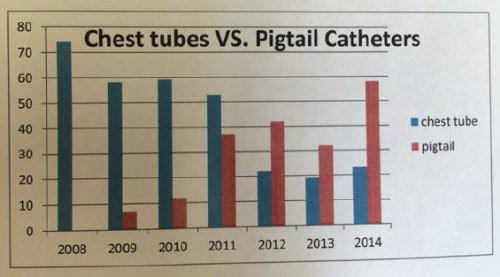

- The group found that their use of pigtails steadily and significantly increased over the years

Bottom line: I’m coming around. The literature does appear to be tilting toward smaller tubes, and this longer-term study helps confirm that. How can this be? Although this is speculation on my part, it probably has to do with the fact that any size tube will drain liquid blood. And probably no size of tube will successfully get all the clot out.

And certainly, smaller tubes are much better tolerated and do not require the degree of sedation that a mega-tube does. The authors suggest that a multi-center trial should be carried out to confirm this. For my part, I’m going to review the literature we have to date and consider modifying my own chest tube policy (see links below).

Questions and comments for the authors/presenters:

- Where did you typically insert the pigtails? Anterior chest or classic chest tube position? Was it consistent?

- Was/is the selection of tube type an attending surgeon specific choice, or did you implement a policy to direct them?

- Did patient injury pattern or body habitus have any part in tube selection?

- What about removal failures? That is, how many had to have a tube replaced, and how many went on to require VATS or other surgical procedure for drainage?

- I enjoyed this provocative paper!

Click here to go the the EAST 2017 page to see comments on other abstracts.

Related posts:

- Sample chest tube management protocol

- Pigtails vs chest tubes – 2013

- Chest tube size – medium vs large tubes

Reference: A prospective study of 7-year experience of using percutaneous 14-French pigtail catheter for traumatic hemothorax at a Level I trauma – size still does not matter. Quick Shot #4, EAST 2017.