About 2.3 million people, or a bit less than 1% of the US population, have atrial fibrillation. This condition is commonly managed with anticoagulants to reduce the risk of stroke. Unfortunately, the elderly represent a large subset of those with a-fib. And the older we get, the more likely we are to fall. About half of those over 80 will fall once a year.

Are all of these elderly patients being treated with anticoagulants appropriately? Several scoring systems have been developed that allow us to predict the likelihood of ischemic stroke. Looking at it another way, they allow us to judge the appropriateness of using an anticoagulant to prevent such an event.

The original CHADS2 score was developed using retrospective Medicare data in the US. The newer CHA2DS2-VASC score used prospective data from multiple countries. However, the accuracy is about the same as the original CHADS2 score. But because the newer system has three more variables, it adds a few more people to the high-risk group who should receive an anticoagulant.

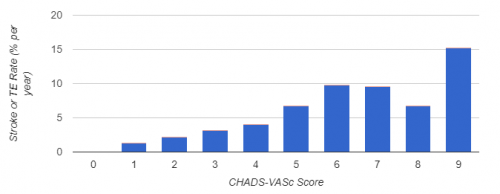

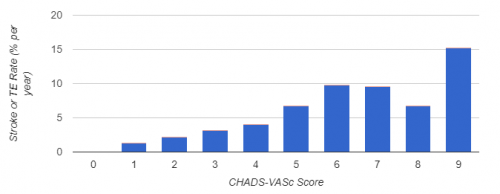

The higher the CHA2DS2-VASC score, the more likely one is to have an ischemic stroke. The threshold to justify anticoagulation seems to vary a bit, with some saying >1 and others going with >2. Here’s a chart that shows how the stroke risk increases.

Stroke risk per year with CHA2DS2-VASC score

Whereas CHA2DS2-VASC predicts the risk of clotting (ischemic stroke), the HAS-BLED score looks at the risk of bleeding. It includes clinical conditions, labile INR, and concomitant use of NSAIDs, aspirin or alcohol, but not a history of falls.

Proper management of atrial fibrillation in the elderly must carefully balance both of these risks to reduce potential harm as much as possible. A HAS-BLED score of >3 indicates a need to clinically review the risk-benefit ratio of anticoagulation. It does not provide an absolute threshold to stop it.

A group at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, a Level I trauma center, retrospectively reviewed their experience with patients who fell while taking an anticoagulant for atrial fibrillation. They calculated CHA2DS2-VASC and HAS-BLED for each and evaluated the appropriateness of their anticoagulation regimen.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 242 patients were reviewed, and the average age was 78

- The average CHA2DS2-VASC score was 5, and the average HAS-BLED was 3

- Only 1.6% were considered to be receiving an anticoagulant inappropriately (CHA2DS2-VASC 0 or 1)

- Nearly 9% of patients were dead 30 days after the fall

Bottom line: The authors found that their population was appropriately anticoagulated. But they also noted that the morbidity and mortality risk was high, and was independent of age and comorbidities.

There are tools available to help us judge whether an elderly patient should be taking an anticoagulant for atrial fibrillation. The tool for predicting bleeding risk, however, is not as good for trauma patients. It ignores the added risk from falling, which is very common in the elderly.

Every patient admitted to the trauma service after a fall should have a critical assessment of their need for anticoagulation. The specific drug they are taking (reversible vs irreversible) should also be examined. If there is any question regarding appropriateness, the primary care provider should be contacted personally to discuss and modify their drug regimen. Don’t just rely on them reading the hospital discharge summary. Falls can be and are frequently fatal, just not immediately. Inappropriate use of anticoagulants can certainly contribute to this problem, so do your part to reduce that risk.

Related links and posts:

Reference: Falls, anticoagulation, and the elderly: are we inappropriately treating atrial fibrillation in this high-risk population? JACS 225(4S1):S53-S54, 2017.