Venous thromboembolism (VTE) and pulmonary embolism (PE) have caused major problems for trauma professionals for at least 50 years. Interestingly, despite advances in chemical and mechanical prophylaxis, the mortality rates for both have remained about the same.

The group at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor looked at the timing of start of VTE chemoprophylaxis. They were curious as to whether the start time made a difference in mortality. They reviewed a collaborative database with 12 years of data, tallying information for all trauma patients who were admitted for at least 48 hours.

Here are the factoids:

- Over 89,000 patients were analyzed; 1.8% developed VTE and 1.9% died (?)

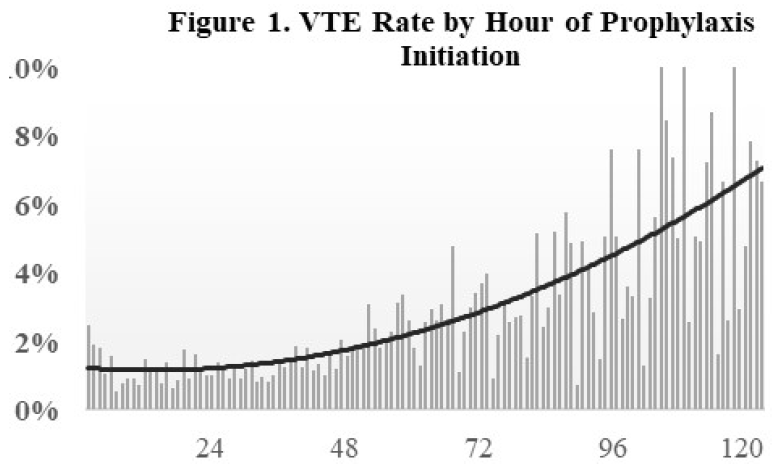

- Delay in starting chemoprophylaxis increased the risk of VTE (see figure)

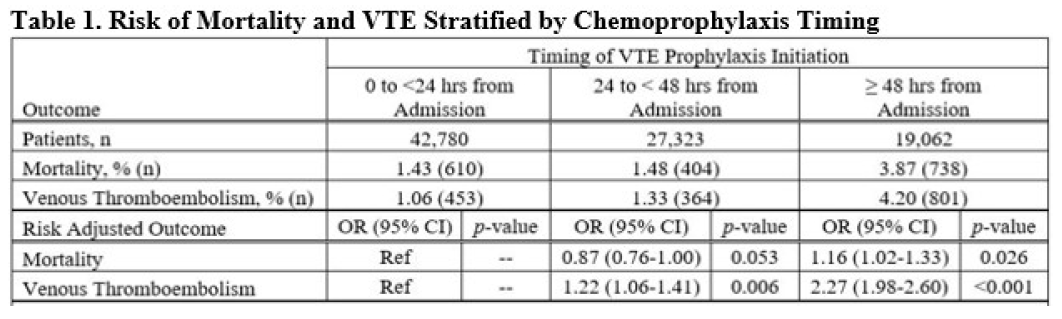

- Delaying chemoprophylaxis beyond 48 hours was associated with increased mortality and increased incidence of VTE

The authors concluded that early initiation of chemoprophylaxis reduces mortality and thrombotic complications.

Here are my comments: Unfortunately, I’m not entirely clear about the details of the abstract. This frequently happens because the authors have to strain to fit all of their ideas in a finite amount of space.

First, it’s a large database study, so it’s difficult to ensure that all the factors you want to study have been included in it. Somebody else designed it years ago, so you get what you get.

I’m a little confused about the incidence of complications and death. They are both about the same number (1.8%). Typically, VTE incidence is a few percent and death from PE is less than 1%. The death number seems high, unless it includes some other type of death.

The VTE incidence vs time graph is very interesting, although the goodness of fit looks a little off toward the right side. It looks like it could easily be a little lower.

Finally, segregating time periods into two 24-hour periods (0-24 hours, 24-48 hours)and one 72-hour plus one (48-120+ hours) seems like it might bias your data. The longer that last period, the greater chance that each patient will develop VTE or die.

Overall, the numbers in Table 1 are noted to be statistically significant, but clinically they appear to be very similar.

Here are some questions for the presenter:

- Please explain the mortality numbers (1.9%). What did these patients die of? A pulmonary embolism? Something unrelated? This number seems high, since it is equal to your VTE incidence.

- Tell us about the risk adjustment you used to calculate mortality rates. What patient factors were available to you? Are there others that might have been helpful to have in the database?

- What tool did you use to fit the curve in Figure 1? The right side looks considerably higher than the data bars would suggest. Please be sure to explain all of the statistical techniques you used, as they were not fully covered in the abstract.

- What was the impact of cramming 3 days of data into your last cohort? Wouldn’t this be expected to yield higher incidences of VTE and death?

I agree that VTE prophylaxis is best started early, but I need a wee bit more information. I’m intrigued by the paper, but I think you will have to spend some time explaining how you designed the analysis so we can all understand.

Reference: Association of timing of initiation of pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis with outcomes in trauma patients. AAST 2020, Oral Abstract #14.