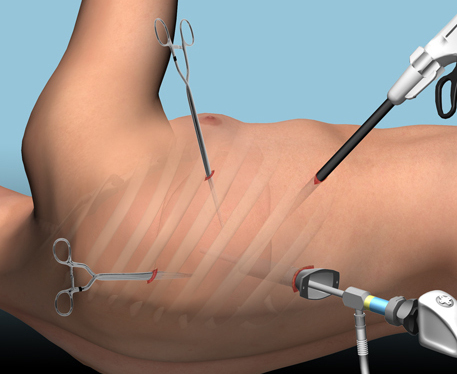

Most solid organ injury practice guidelines include angioembolization in part of the pathway. But very few require re-imaging at any point to see how the liver or spleen are coming along.

But every once in a while another condition arises, or symptoms worsen unexpectedly, causing us to get another CT scan that includes the abdomen and pelvis. And sometimes we see things that we wouldn’t normally see, like air bubbles in the organ that was embolized.

So what is okay, and what requires some kind of intervention? Our friends at ShockTrauma in Baltimore looked at this in 2001 and can provide some pretty good guidance. They reviewed patients who underwent CT scan both before and after embolization over about 2.5 years. They performed the post-embolization scans for specific indications like fevers, elevated WBC count (!), increasing abdominal pain, or an episode of hypotension. A total of 53 patients were studied.

Here are the factoids:

- 24 patients underwent embolization of the main splenic artery, 22 had selective embolization of part of the spleen, and 7 had both

- Splenic infarcts occurred in 63% of patients with main artery embolization, but were large (> 50% of the parenchyma) in only 20% of those

- Infarcts occurred in 100% of selective embolizations, but were small (< 50%) in 93% of cases

- Infarcts occurred in 71% of patients with both main and selective embolization, and most were small (80%)

- Seven (13%) patients developed gas bubbles in the spleen, and was usually present for 1-7 days before disappearing

- One patient developed increasing gas with pneumoperitoneum and underwent splenectomy for a splenectomy for abscess

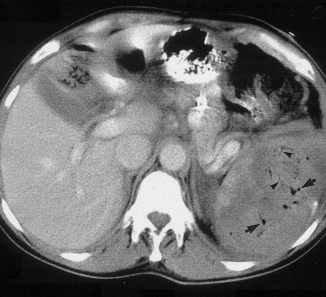

This picture that shows tiny bubbles in the spleen parenchyma that represent “normal” gas after embolization:

And the following one shows an air/fluid collection in the spleen that indicates an abscess:

Bottom line: Tiny bubbles in the spleen (and probably the liver) occur normally after angioembolization. They usually develop within an area of infarction, and most are benign. It is possible for them to evolve into a splenic abscess, but unlikely. Many embolization patients develop fevers at some point, and most have an elevated WBC count. So in most cases, you can ignore this incidental finding, as long as your patient has mild symptoms.

However, if the patient develops high fevers, very elevated WBC (> 25K), increasing abdominal or flank pain, and the spleen develops an air/fluid level, an abscess is forming. Despite what your radiologist might suggest, catheter drainage is not a good idea. The tubes are too small to remove the slurry that is generally found within the abscess. A trip to the OR is the only effective treatment, and splenectomy is generally the only option.

Related posts:

Reference: CT Findings after Embolization for Blunt Splenic Trauma. J Vasc Intervent Radiol 12(2):209-214, 2001.