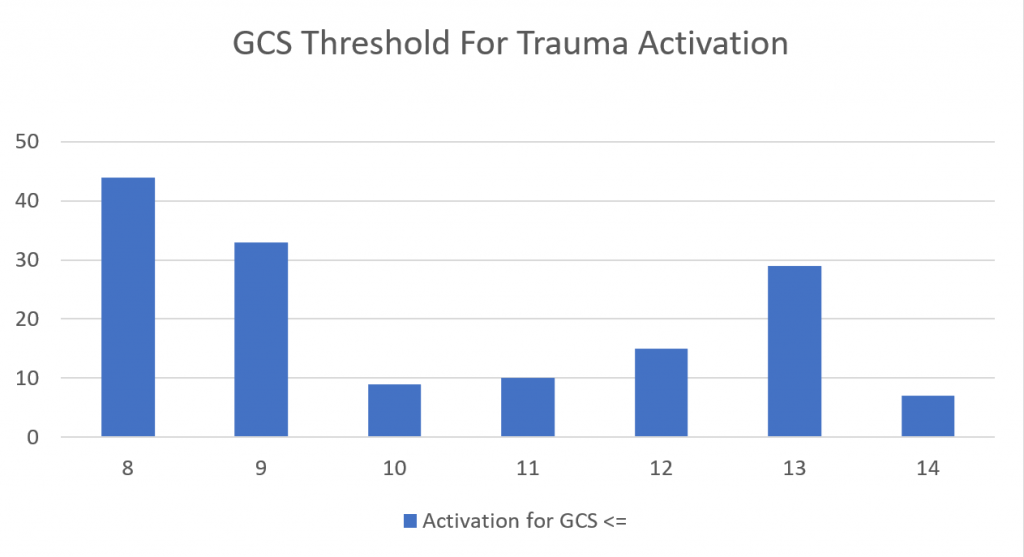

One of the more common reasons for transfer to a higher level trauma center these days is the “mild or minimal TBI.” Technically, this consists of any patient with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 14 or 15. A transfer is typically requested for observation or neurosurgical consultation, or because the clinicians at the initial hospital are not comfortable looking after the patient.

Is this really necessary? With the number of ground level falls approaching epidemic proportions, transferring all these patients could begin to overwhelm the resources of high level trauma centers. The surgical group at Carolinas Medical Center examined their experience with a simple scoring system they designed to predict high risk minor TBI patients, and thus suitability for transfer. Here is their checklist:

| Category A |

|

| Category B |

|

| SAH = subarachnoid hemorrhage, SDH = subdural hemorrhage, IPH = intraparenchymal hemorrhage |

Patients were considered to be low risk if they had only one or two category A lesions. If they had more than two, or any Category B lesions, they were higher risk and transfer was considered justified.

The authors retrospectively reviewed their experience with these patients over a three year period. They followed patients to see if they needed neurosurgical intervention, and evaluated the cost savings of avoiding selective transfers based on their criteria.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 2120 patients were studied, with 68% low risk and 32% high risk

- Two of the low risk patients (0.14%) ultimately required neurosurgical intervention, compared to 21% of high risk patients

- Mean age (56), and patients taking anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents were the same in the two groups, about 2-3% for each

- System saving by avoiding EMS transfer costs would have been $734K had the low risk patients been kept at the initial hospital

Bottom line: This study was presented as a Quick Shot paper at this year’s Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma meeting, so there are some key details missing. Was there an association between anticoagulation or antiplatelet agent and two failures in the low risk group? What were they, and what intervention did they require?

If this data holds up to publication, then it may provide a useful tool for deciding to keep minimal TBI patients at the local hospital. This is usually far more convenient for the patient and their family, but would require additional education of the clinicians at that hospital to help them become comfortable managing these patients.

We use a similar tool within our Level I trauma center to decide which patients require a neurosurgical consultation. Since the low risk patients almost never require intervention, our trauma service provides comprehensive management while in hospital, and arranges for TBI clinic followup post-discharge. You can view and download a copy using the link below.

Link: Regions Hospital SAH/IPH/Skull fracture practice guideline

Reference: Redefining minimal traumatic brain injury (MTBI): a novel CT criteria to predict intervention. Quick Shot Paper #48, EAST 2019.