Here’s a quick primer on grading spleen injury. It’s only 4 minutes long, so enjoy!

Category Archives: Abdomen

Spleen Embolization In Adolescents?

Modern day nonoperative management of solid organ injury in adults came to be due to its success rate in children. But if you look at the practice guidelines for adults, they frequently include a path for angioembolization in certain patients. In children, embolization is almost never recommended.

But what about that gray zone where children transition to adults? How young is too young to embolize? Or how old is too old not to consider it?

The adult and pediatric trauma groups at Wake Forest looked at this question by reviewing their respective trauma registry data. They looked specifically at patients age 13-18 who presented with a blunt splenic injury over a 8.5 year period. About halfway through this period, adult patients (> 16 years) were sent for embolization not only for pseudoaneurysm or extravasation, but also for high grade injury (> grade 3). Patients under age 16 were managed by the pediatric trauma team, and those 16 and older by the adult team.

Here are the factoids:

- Of the 133 patients studied, 59 were “adolescents” (age 13-15) and 74 were “adults” (16 or older)

- Patients managed by the adult team sent 27 of their 74 patients for angiography

- Those managed by the pediatric team were never sent to angiography

- The failure rate for nonoperative management was statistically identical, about 4% in adults and 0% in adolescents

- For high grade injuries, the adult team sent 27 of 34 patients to IR, whereas the pediatric team sent none of 36. Once again, failure rate was identical.

Bottom line: We already know that too many adult trauma centers send too many younger patients to angiography for solid organ injury. This study tries to tease out when a child becomes an adult, and therefore when angiography should begin to be considered. And basically, it showed that through age 15, they can still be considered as and treated like children, without angiography.

But remember, these numbers are relatively small, so take this work with a grain of salt. If you are managing a younger patient nonoperatively, and they continue to show evidence of blood loss (ongoing fluid/blood requirements, increasing heart rate), angiography may be helpful in avoiding laparotomy as long as your patient remains hemodynamically stable. But consult with your friendly neighborhood pediatric surgeon first.

Related posts:

- Video: how to grade spleen injury

- Solid organ injury tips

- Please, no bedrest after pediatric spleen injury

Reference: The Spleen Not Taken: Differences in management and outcomes of blunt splenic injuries in teenagers cared for by adult and pediatric trauma teams in a single institution. J Trauma, in press, May 2017.

Post-Embolization Syndrome In Trauma

A reader requested that I write about post-embolization syndrome. Not being an oncologist or oncologic surgeon, I honestly had never heard about this before, let alone in trauma care. So I figured I would read up and share. And fortunately it was easy; there’s all of one paper about it in the trauma literature.

Post-embolization syndrome is a constellation of symptoms including pain, fever, nausea, and ileus that occurs after angio-embolization of the liver or spleen. There are reports that it is a common occurrence (60-80%) in patients being treated for cancer, and there are a few papers describing it in patients with splenic aneurysm. But only one for trauma.

Children’s Hospital of Boston / Harvard Medical School retrospectively reviewed 12 years of their pediatric trauma registry data. For every child with a spleen injury who underwent angio-embolization, they matched four others with the same grade of injury who did not. A total of 448 children with blunt splenic injury were identified, and (thankfully) only 11 underwent angio-embolization. Nine had ongoing bleeding despite resuscitation, and two had developed splenic pseudoaneursyms.

Here are the factoids:

- More of the children who underwent embolization had extravasation seen initially and required more blood products. They also had longer ICU (3 vs 1 day) and hospital stays (8 vs 5 days). Not surprising, as that is why they had the procedure.

- 90% of embolized kids had an ileus vs 2% of those not embolized, and they took longer to resume regular diet (5 vs 2 days)

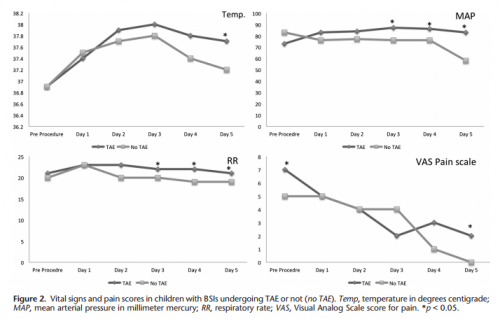

- Respiratory rate and blood pressure were higher on days 3 and 4 in the embolized group, as was the temperature on day 5 (? see below)

- Pain was higher on day 5 in the embolized group (? see below again)

Bottom line: Sorry, but I’m not convinced. Yes, I have observed increased pain and temperature elevations in patients who have been embolized. Some have also had an ileus, but it’s difficult to say if that’s from the procedure or other injuries. And this very small series just doesn’t have enough power to convince me of any clinically significant differences in injured children.

Look at the results above. “Significant” differences were only identified on a few select days, but not on the same days across charts. And although the authors may have demonstrated statistical differences, are they clinically relevant? Is a respiratory rate of 22 different from 18? A temp of 37.8 vs 37.2? I don’t think so. And length of stay does not reveal anything because the time in the ICU or hospital is completely dependent on the whims of the surgeon.

I agree that post-embolization syndrome exists in cancer patients. But the findings in trauma patients are too nondescript. They just don’t stand out well enough on their own for me to consider them a real syndrome. As a trauma professional, be aware that your patient probably will experience more pain over the affected organ for a few days, and they will be slow to resume their diet. But other than supportive care and patience, nothing special need be done.

Related posts:

- Solid organ injury tips

- Contrast blush in children

- Bedrest after pediatric solid organ injury? Really?

Reference: Transarterial embolization in children with blunt splenic injury

results in postembolization syndrome: A matched

case-control study. J Trauma 73(6):1558-1563, 2012.

Incidental Finding: Gas In The Spleen After Embolization

Most solid organ injury practice guidelines include angioembolization in part of the pathway. But very few require re-imaging at any point to see how the liver or spleen are coming along.

But every once in a while another condition arises, or symptoms worsen unexpectedly, causing us to get another CT scan that includes the abdomen and pelvis. And sometimes we see things that we wouldn’t normally see, like air bubbles in the organ that was embolized.

So what is okay, and what requires some kind of intervention? Our friends at ShockTrauma in Baltimore looked at this in 2001 and can provide some pretty good guidance. They reviewed patients who underwent CT scan both before and after embolization over about 2.5 years. They performed the post-embolization scans for specific indications like fevers, elevated WBC count (!), increasing abdominal pain, or an episode of hypotension. A total of 53 patients were studied.

Here are the factoids:

- 24 patients underwent embolization of the main splenic artery, 22 had selective embolization of part of the spleen, and 7 had both

- Splenic infarcts occurred in 63% of patients with main artery embolization, but were large (> 50% of the parenchyma) in only 20% of those

- Infarcts occurred in 100% of selective embolizations, but were small (< 50%) in 93% of cases

- Infarcts occurred in 71% of patients with both main and selective embolization, and most were small (80%)

- Seven (13%) patients developed gas bubbles in the spleen, and was usually present for 1-7 days before disappearing

- One patient developed increasing gas with pneumoperitoneum and underwent splenectomy for a splenectomy for abscess

This picture that shows tiny bubbles in the spleen parenchyma that represent “normal” gas after embolization:

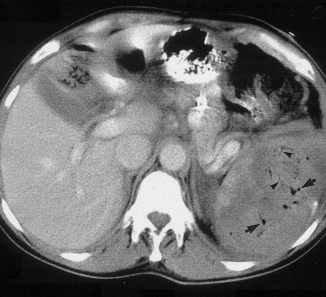

And the following one shows an air/fluid collection in the spleen that indicates an abscess:

Bottom line: Tiny bubbles in the spleen (and probably the liver) occur normally after angioembolization. They usually develop within an area of infarction, and most are benign. It is possible for them to evolve into a splenic abscess, but unlikely. Many embolization patients develop fevers at some point, and most have an elevated WBC count. So in most cases, you can ignore this incidental finding, as long as your patient has mild symptoms.

However, if the patient develops high fevers, very elevated WBC (> 25K), increasing abdominal or flank pain, and the spleen develops an air/fluid level, an abscess is forming. Despite what your radiologist might suggest, catheter drainage is not a good idea. The tubes are too small to remove the slurry that is generally found within the abscess. A trip to the OR is the only effective treatment, and splenectomy is generally the only option.

Related posts:

Reference: CT Findings after Embolization for Blunt Splenic Trauma. J Vasc Intervent Radiol 12(2):209-214, 2001.

EAST 2017 #6: FAST Exam After Rolling to the Right

The FAST exam is an integral part of trauma evaluation. Even after experience and credentialing of providers, there tends to be some variability in performance. This is especially true when the abnormal findings (or amount of fluid present) is relatively small.

Can we improve this by doing something as simple as using gravity to help? When the patient is supine, fluid tends to pool in the pelvis, where interpretation is a little more complicated. The surgery program at Guthrie/Packer Hospital created a small pilot study to see if they might improve the sensitivity of FAST by rolling patients to their right briefly, before returning to the supine position and performing the exam.

They enrolled seven participants who were already undergoing peritoneal dialysis (PD), so there was easy access to the peritoneal cavity for administration of known amounts of free fluid. First, each patient was drained of any residual dialysate via their PD catheter. They then underwent a baseline FAST exam. Next, they were placed in the right lateral decubitus position for 30 seconds, then placed supine again and the FAST was repeated. Each patient then had 50cc of dialysate infused, and the process was repeated until a positive FAST was obtained.

Here are the factoids:

- Of the seven patients recruited, one was excluded because the initial FAST was equivocal due to body habitus and polycystic kidney disease

- A maximum of 3 aliquots were given (150cc max)

- Two patients became positive after right side down before any additional fluid was infused

- None of the four remaining patients had a positive FAST after infusion of any aliquot in the supine position

- All four became positive after the right side down maneuver, two after 50cc, one after 100cc, and one after 150cc

Bottom line: The authors conclude that this may be a valuable technique to help detect smaller quantities of fluid than we normally do. I’m not so sure. First, it’s a tiny study in a patient group that is very different from trauma. And it’s impossible to quantify how much dialysate was left after initial drainage of the PD catheter. Finally, we know that FAST can’t “see” small quantities of fluid, but we have constructed our management algorithms around this fact. So we have a good idea of when we should do further imaging or run off to the operating room. Making this test more sensitive may skew these practice guidelines toward doing more (and potentially unneeded) imaging and surgery.

Questions and comments for the authors/presenters:

- Did you record the volumes and administration times of dialysate given prior to the study? This may correlate with the initial positives and volumes needed to give a positive result.

- Similarly, did you look at BMI and body habitus to see if there might be a correlation?

- Are you planning any type of followup study, as you suggested in the abstract?

Click here to go the the EAST 2017 page to see comments on other abstracts.

Related posts:

- FAST is fast, and FAST is last, Part 1

- Fast is fast, and FAST is last, Part 2

- Should extended FAST be a standard part of trauma activation?

- Video: how to do an extended FAST (eFAST) (funny!)

Reference: Can we be faster? FAST examination after rolling to the right dramatically increases sensitivity. Quick Shot #7, EAST 2017.