A New Method For Killing Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria

IBM and the Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology have developed a novel way of wiping out antibiotic resistant bacteria like MRSA. They created a type of nanoparticle that is activated by contact with water. When this occurs, it self-assembles into a new polymer structure that is attracted to infected cells and bacteria, but not healthy cells.

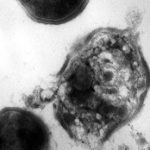

Changes in electrostatic charge on the cell surface attracts the nanoparticles, which then physically break through the cell walls and membranes of bacteria. The nanoparticles then degrade and are excreted.

Bottom line: This is a very exciting line of research. Bacteria multiply and evolve rapidly, sharing genetic information that allows them to change their biochemistry and become resistant to our usual antibiotics. Since the destructive process used by these nanoparticles is purely physical and not biochemical, it will be extremely difficult for any type of resistance to develop. This is an important advance in our efforts to control pathogens.

Reference: Biodegradable nanostructures with selective lysis of microbial membranes. Nature Chemistry, April 3, 2011 (online).