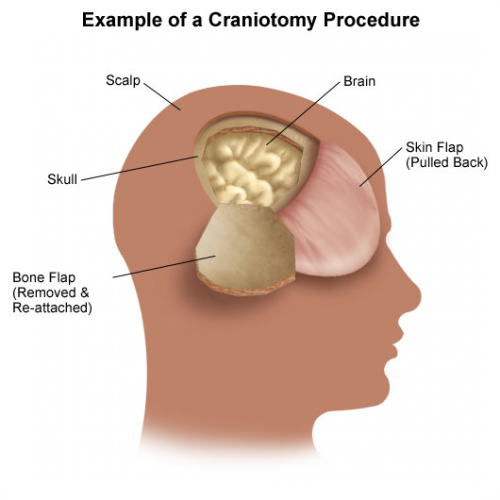

Patients with severe TBI frequently undergo surgical procedures to remove clot or decompress the brain. Most of the time, they undergo a craniotomy, in which a bone flap is raised temporarily and then replaced at the end of the procedure.

But in decompressive surgery, the bone flap cannot be replaced because doing so may increase intracranial pressure. What to do with it?

There are four options:

- The piece of bone can buried in the subcutaneous tissue of the abdominal wall. The advantage is that it can’t get lost. Cosmetically, it looks odd, but so does having a bone flap missing from the side of your head. And this technique can’t be used as easily if the patient has had prior abdominal surgery.

2. Some centers have buried the flap in the subgaleal tissues of the scalp on the opposite side of the skull. The few papers on this technique demonstrated a low infection rate. The advantage is that only one surgical field is necessary at the time the flap is replaced. However, the cosmetic disadvantage before the flap is replaced is much more pronounced.

3. Most commonly, the flap is frozen and “banked” for later replacement. There are reports of some mineral loss from the flap after replacement, and occasional infection. And occasionally the entire piece is misplaced. Another disadvantage is that if the patient moves away or presents to another hospital for flap replacement, the logistics of transferring a frozen piece of bone are very challenging.

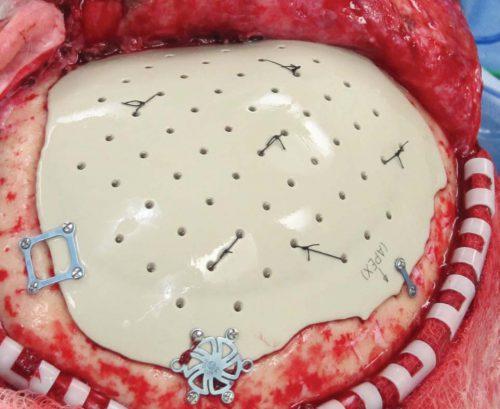

4. Some centers just throw the bone flap away. This necessitates replacing it with some other material like metal or plastic. This tends to be more complicated and expensive, since the replacement needs to be sculpted to fit the existing gap.

So which flap management technique is best? Unfortunately, we don’t know yet, and probably never will. Your neurosurgeons will have their favorite technique, and that will ultimately be the option of choice.

Reference: Bone flap management in neurosurgery. Rev Neuroscience 17(2):133-137, 2009.