The Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) has been in use for more than 40 years. Since that 40th anniversary a few years back, there has been talk of updating this tried and true system. But where did this scale come from? How was it devised? And why are we looking to update it now? I’ll dig into this topic over my next several posts.

The original paper describing the GCS was published in 1974 by Graham Teasdale and Bryan Jennett. They were neurosurgeons at the Institute of Neurologic Sciences in Glasgow, Scotland (of course) and were based in the Southern General Hospital. Until this paper was published, each report in the literature described its own assessment of level of consciousness. Most divided the spectrum into various steps noted between fully alert and comatose. Unfortunately, these systems were confusing, and they varied from 3-17 steps! There was just no consensus. Some relied on a comprehensive neurologic exam, including brainstem function tests. However, none of these were really designed for repeated bedside assessment.

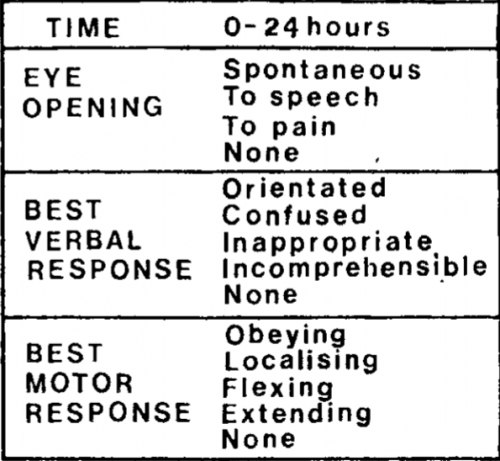

Teasdale and Jennett settled on three simple areas to examine: eye-opening, motor response, and verbal response. They selected easily observable responses for each of these components. Here is a copy of the original scale:

Notice that this differs from the current-day score. The motor response did not have a “withdrawal” option, so the maximum score was only 14! But that didn’t matter much at the time; the individual components were graphed out over time for inspection. A total score was not generally calculated.

Teasdale and Jennett found that inter-rater reliability for this system was excellent, compared to a 25% discrepancy for other less objective systems in use at the time. This led to its rapid adoption over the coming years.

In my next post, I’ll describe how GCS came to be used over the ensuing years.