The next paper presentation I’ll review from the upcoming EAST Annual Assembly is from a consortium of six US trauma programs, and appears to be under the direction of faculty at the McGovern Medical School in Houston. They recognized that rates of damage control laparotomy (DCL) vary widely throughout the US. In part, this is due to the lack of hard and fast indications for the application of this procedure. This procedure is used in cases where patient physiology (or trends in that physiology) would suggest that persisting with an open body cavity would lead to hypothermia, coagulopathy, additional injury, or death.

This study entailed the prospective review of every DCL performed at the centers over a one year period. Each was adjudicated by a majority faculty vote as to whether it would have been safe and appropriate to perform a definitive laparotomy (DL) instead. DL means that all injuries are fixed and the abdomen is closed.

Here are the factoids:

- 872 trauma laparotomies were performed: 209 DCL and 639 DL. There were 24 intraoperative deaths.

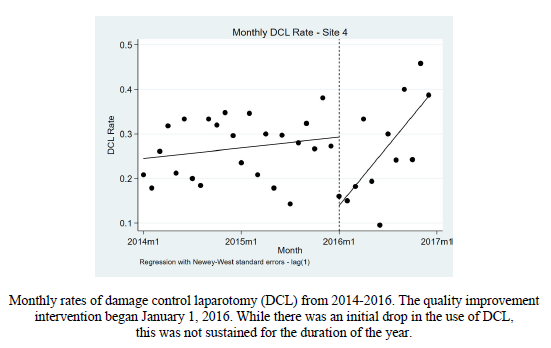

- There was no change in DCL rate compared to historical controls for 5 of the 6 centers (see diagram)

- One center had an initial reduction in DCL rate, but this disappeared throughout the rest of the study

- The voting group found consensus in recommending DCL with hemodynamic instability or if packing was required, but could not agree on the need for second look procedures

Overall, this intervention (reviewing each and every damage control procedure immediately after) did not decrease the DCL rate as hoped. The authors cited the second look laparotomy disagreement as a possible target to improve results.

Here are some questions for the authors and presenter to consider in advance to help them prepare for audience questions:

- All DCLs are not the same. Six different centers were studied, each with their own DCL popluation. What was the blunt:penetrating mix for each? What were the specific mechanisms and injuries sustained? ISS? It could be that the study group was not homogeneous, making it more difficult to judge appropriateness.

- Was the study powered well enough to detect differences? The total number of DCL cases was only 209, or 35 per center. And of course, some had more, some less. In our original DCL paper from Penn, the clinical significance first showed up only in the subset of most severely injured penetrating injury patients. Did you have enough patients?

- What exactly was the intervention that would drive down the DCL rate? Although this is (kind of) a prospective project, the analysis of each case and the consensus vote took place after each procedure. Was this done at each institution, or only by the research group at the mother ship? How did the results get disseminated to all surgeons so that they could apply the findings to their next trauma laparotomy?

- Look at the outlier. This is always valuable. Why was center #4 so much lower at the beginning of the study period compared to the one year historical control? Were their laparotomy numbers lower? Patient/injury mix different? Did you interview that group to see what their insights were? This is one of the most interesting findings, in my opinion.

I’ll be sitting in the front row for this one!

Reference: Better understanding the utilization of damage control laparotomy: a multiinstitutional quality improvement project. EAST 2019, Paper #12.