Solid organ injury is one of the more common manifestations of blunt abdominal trauma. Most trauma centers have some sort of practice guideline for managing these injuries. Frequently, interventional radiology (IR) and angioembolization (AE) are part of this algorithm, especially when active bleeding is noted on CT scan.

So it makes sense that getting to IR in a timely manner would serve to stop the bleeding sooner and help the patient. But in most hospitals, interventional radiology is not in-house 24/7. Calls after hours require mobilization of a call team, which may be costly and take time.

For this reason, it is important to know if rapid access to angioembolization makes sense. Couldn’t the patient just wait until the start of business the next morning when the IR team normally arrives?

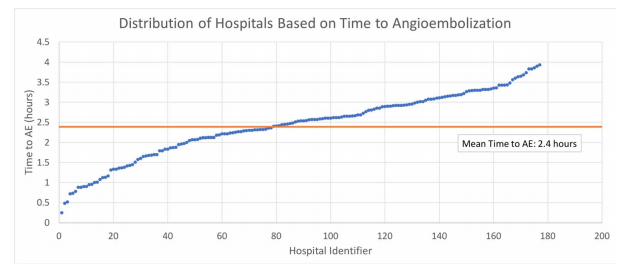

The group at the University of Arizona at Tucson tackled this problem. They performed a 4-year retrospective review of the TQIP database. They included all adult patients who underwent AE within four hours of admission. Outcome measures were 24-hour mortality, blood product usage, and in-hospital mortality.

Here are the factoids:

- Out of over a million records in the database, only 924 met the inclusion criteria

- Mean time to AE was 2 hours and 22 minutes, with 92% of patients getting this procedure more than an hour after arrival

- Average 24-hour mortality was 5%. Mortality by hours to AE was as follows:

- Within 1 hour: 2.6%

- Within 2 hours: 3.6%

- Within 3 hours: 4.0%

- Within 4 hours: 8.8%

- There was no difference in the use of blood products

The authors concluded that delayed angioembolization for solid organ injury is associated with increased mortality but no increase in blood product usage. They recommend that improving time to AE is a worthy performance improvement project.

Bottom line: This study has the usual limitations of a retrospective database review. But it is really the only way to obtain the range of data needed for the analysis.

The results seem straightforward: early angioembolization saves lives. What puzzles me is that these patients should be bleeding from their solid organ injury. Yet longer delays did not result in the use of more blood products.

There are two possibilities for this: there are other important factors that were not accounted for, or the sample size was too small to identify a difference. As we know, there are huge variations in how clinicians choose to administer blood products. This could easily account for the apparent similarities between products given at various time intervals to AE.

My advice? Act like your patient is bleeding to death. If the CT scan indicates that they have active extravasation, they actually are. If a parenchymal pseudoaneurysm is present, they are about to. So call in your IR team immediately! Minutes count!

Reference: Angioembolization in intra-abdominal solid organ injury:

Does delay in angioembolization affect outcomes? J Trauma 89(4):723-729, 2020.