Traumatic hemothorax is an interesting problem. Sometimes it clots, sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes it sticks to the lung and causes a restrictive problem, sometimes it doesn’t. And even if it doesn’t fuse to the lung, having a moderate volume of retained blood can create significant functional problems.

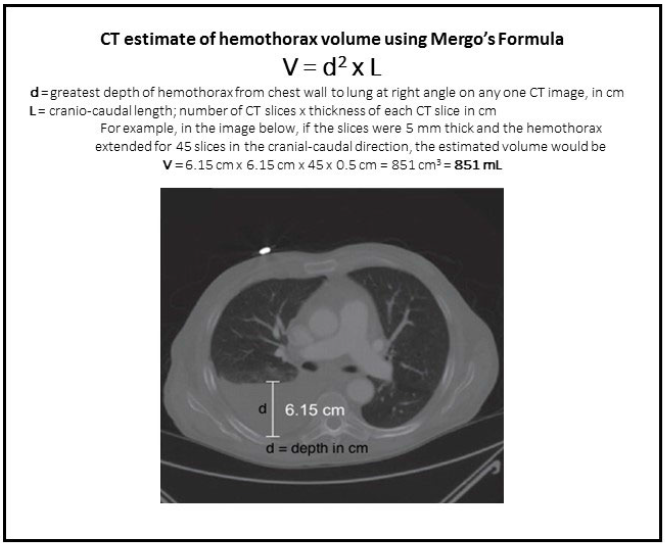

What if we could predict which hemothoraces would progress to retained hemothorax so we could intervene sooner and avoid complications and potential wasted time in the hospital? An EAST multi-institutional trial explored a possible technique for doing just that, postulating that an initial large volume hemothorax (HTX) would correlate with development of retained HTX. This study used data collected prospectively from 17 US trauma centers, and involved the use of Mergo’s formula to calculate the size of the HTX. This technique essentially estimates the volume of a cylinder that fits inside the largest diameter of the HTX seen on CT scan, extending the entire length of the thorax. Although this technique will underestimate the volume at the largest part of the HTX, it overestimates it above and below this point, so it probably all evens out. Roughly.

Here are the factoids:

- 985 patients were enrolled and 1033 HTX were measured

- Patients who developed retained HTX (defined as blood in the chest requiring intervention or subsequent identification of HTX by CT) were more likely to have penetrating trauma, pulmonary contusion, and had their HTX seen on initial chest x-ray (CXR)

- Chest abbreviated injury score (AIS) was higher in patients with retained HTX, and their calculated HTX volume was larger

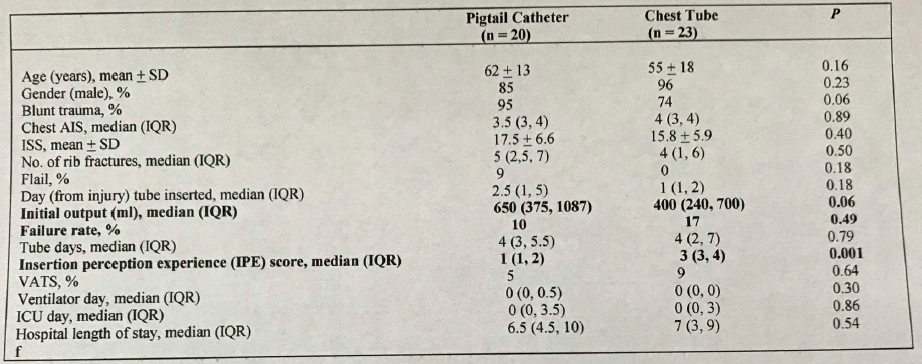

- Chest tube size did not correlate with development of retained HTX

- The authors concluded that patients who developed retained HTX had a lower initial hematocrit, higher chest AIS, and large volume seen on CT

Here are some questions for the authors and presenter to consider in advance to help them prepare for audience questions:

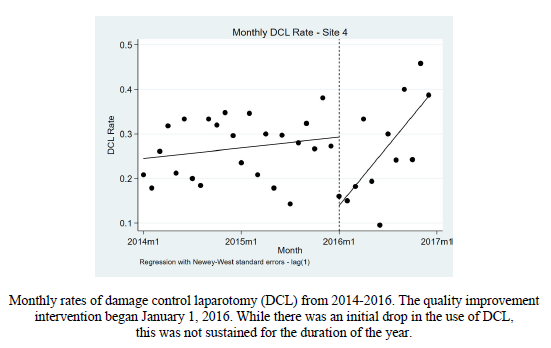

- When and over what period of time was this data collected? It was not stated in the abstract. Very old or long-running data sets run the risk of technology (CT scan resolution) or practice (pigtail vs chest tube) changes.

- Couldn’t the hematocrit and chest AIS factors be red herrings? Did this study look at all the other injuries that could have decreased the hematocrit or just focus on the chest injury? And the chest AIS automatically increases from 3 to 4 as the volume of the HTX increases. Could this skew your analysis?

- One of the definitions of retained HTX (need for intervention) depends on clinical judgement and practice habits, which probably differ at the various trauma centers enrolled.

- Only odds ratios were listed in the abstract. Even though the HCT and AIS numbers are statistically significantly different, I can’t tell if they are clinically significant. Be sure to share your means and standard deviation/error during your presentation.

- Did you lump pigtail catheters in with regular chest tubes? And did you look at the distribution of chest tube sizes? If all were large it would be hard to come to a good conclusion about size.

- What about trauma centers who do not use CT on every trauma patient? Do we really need to CT someone who falls down, breaks a few ribs, and has a visible HTX on CXR?

- Big picture: so what do we do now based on your findings? How do we plan re-imaging and potential surgical intervention in these patients?

This is very interesting work, and I look forward to the presentation!

Reference: Predictors of post-traumatic retained hemothorax: results of an EAST multi-institutional trial. EAST 2019 Paper #14.