Well, it took me a month to figure out that one of my pop quiz answers was posted to the wrong area! The link provided with the tweet would have gotten you to it, but those who were following along on tumblr may have been mystified. Here’s the answer again.

Here’s a link to the original post/quiz.

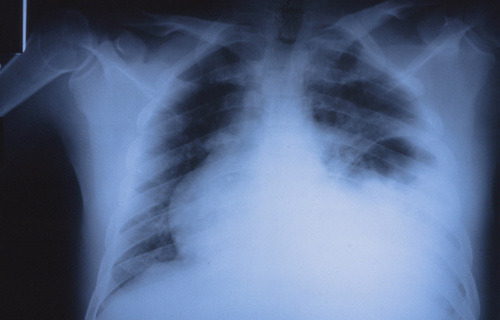

So the question was to guess the exact mechanism of injury given the x-ray below.

The image shows a stomach bubble located in the left chest, indicating a left sided diaphragm rupture. In countries with left sided drivers, this is a classic injury from a t-bone type impact directly on the driver side door. The arm rest is driven into the driver’s flank, or on occasion the driver is partially ejected through the window. The impact raises abdominal pressure abruptly and can push the abdominal contents (typically stomach, followed by spleen) through the weakest area of the diaphragm.

Practical tip: These patients may present with tachypnea and decreased breath sounds on the left side. The usual reflex is to insert a chest tube, which is unneeded and won’t help in this case. What the patient really needs is an NG tube to help their breathing (and an immediate trip to the OR). So if you encounter this clinical combination plus a significant left sided impact (car crash, pedestrian struck), get a chest x-ray first if the patient’s condition will tolerate it.

And again, hats off to precordialthump for getting it exactly right!