An anonymous user recently asked about decision-making with regard to anticoagulation reversal. Specifically, they were interested in using prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) vs activated Factor VII (FVIIa). I’ve done a little homework on this question, and am going to include some information on the use of fresh frozen plasma (FFP), too.

Unfortunately, there’s not a lot of good data out there comparing the three. Enthusiasm for using FVIIa is waning because it is extremely expensive and the risk/benefit ratio is becoming clearer with time (more risk and less benefit than originally thought). PCC is attractive because it provides most of the same coagulation factors as FFP, but with far less volume. However, it is very expensive, too.

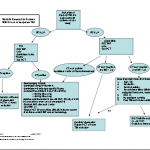

What to do? One of the best papers out there comes from the UK, where they looked at the cost effectiveness of PCC vs FFP in warfarin reversal. They reviewed a year’s worth of National Health Service patients from the standpoint of what it costs to gain a year of life after hemorrhage. They found that the cost was £1000-£2000 per life-year, and £3000 per quality adjusted life-year. This was more cost effective than using FFP. Unfortunately, I do not have access to the full text to review the details.

PCC has only been compared to FFP in the treatment of hemophilia, so it’s not possible to draw any conclusions. The course of therapy for perioperative management of hemophiliacs is lengthy (meaning hideously expensive), and there was a cost-savings seen ($400,000)! Since we use only short duration therapy in trauma patients, the savings will be far less.

Bottom line: PCC is probably as effective as FFP, with less risk of volume overload. It is probably more cost effective as well. As the population of people that are placed on warfarin ages and becomes more susceptible to volume overload from plasma infusions, I think that PCC is going to become the reversal agent of choice. Use of Factor VIIa will continue to wane. However, someone needs to do some really good studies so we don’t get suckered.

Related posts:

Reference: Modeling the cost-effectiveness of prothrombin complex concentrate compared with fresh frozen plasma in emergency warfarin reversal in the United Kingdom. Clinical Therapeutics 32(14):2478-2493, 2010.