Simple Tracheobronchial Injury

Injury to the airway has the potential to be a catastrophe, with rapid deterioration and death. Occasionally the injury is less dramatic with a slow air leak, but it can still present a diagnostic and management challenge.

These lower airway injuries can occur after either blunt or penetrating trauma. The penetrating ones are relatively simple to diagnose because the wound tract is known and, if stable, a trip to CT demonstrates the problem area.

Blunt lower airway injury is a bit trickier. These typically require a high energy mechanism, such as a motor vehicle crash. Up to half of these injuries are not diagnosed immediately. Typically, unexpected air on the chest xray is identified. Less commonly, subcutaneous emphysema appears and prompts more investigation.

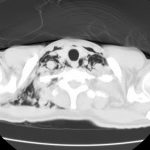

Previously, the gold standard for diagnosis was bronchoscopy. CT has gotten so good that even smaller bronchial injuries can be identified, so CT is now the diagnostic study of choice. Management of injuries that do not threaten the airway consists of close observation. Smaller ones may heal on their own without complication. Larger injuries usually continue to leak and do not heal. If ventilation problems develop, either from persistent large pneumothorax or large amounts of air dissecting into the neck, intubation will be required. However, positive pressure may exacerbate the problem, so low pressure ventilation modalities must be used. A prompt trip to the OR will be required in such cases.

Bottom line: Simple (slow leak) tracheobronchial injuries are uncommon, but are seen after major blunt trauma and any kind of thoracic penetrating injury. The best way to diagnose the exact problem and location is thin cut CT of the chest. Injuries with minor clinical dysfunction can be admitted to the trauma service and observed. If the leak does not resolve, or causes breathing problems, a thoracic surgeon will very likely need to intervene to repair the problem.

Related posts: