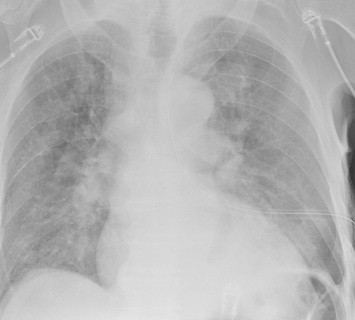

How big is too big? That has been the question for a long time as it applies to pneumothorax and chest tubes. For many, it is a math problem that takes into account the appearance on chest x-ray, the physiology of the patient, and their ability to tolerate the pneumothorax based on any pre-existing medical conditions.

The group at Froedtert in Milwaukee has been trying to make this decision a bit more objective. They introduced the concept of CT based size measurement using a 35mm threshold at this very meeting three years ago. Read my review here. My criticisms at the time centered around the need to get a CT scan for diagnosis and their subjective definition of a failure requiring chest tube insertion. The abstract never did make it to publication.

The authors are back now with a follow-on study. This time, they made a rule that any pneumothorax less than 35mm from the chest wall would be observed without tube placement. The performed a retrospective review of their experience and divided it into two time periods: 2015-2016, before the new rule, and 2018-2019, after the new rule. They excluded any chest tubes inserted before the scan was performed, those that included a sizable hemothorax, and patients placed on a ventilator or who died.

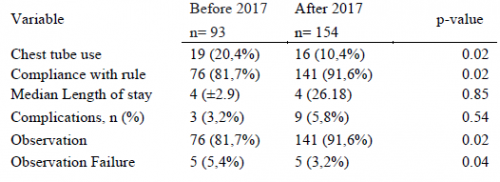

Here are the factoids:

- There were 93 patients in the early period and 154 in the later period

- Chest tube use significantly declined from 20% to 10% between the two periods

- Compliance with the rule significantly increased from 82% to 92%

- There was no difference in length of stay, complications, or death

- Observation failure was marginally less in the later period, and statistical significance depends on what method you use to calculate it

- Patients in the later group were 2x more likely to be observed (by regression analysis)

The authors concluded that the 35mm rule resulted in a two-fold increase in observation and decreased the number of unnecessary CT scans.

Bottom line: I still have a few issues with this series of abstracts. First, decision to insert a chest tube requires a CT scan in a patient with a pneumothorax. This seems like extra radiation for patients who may not otherwise fit any of the usual blunt imaging criteria. And, like their 2018 abstract, there is no objective criteria for failure requiring tube insertion. So the number of insertions can potentially be quite subjective based on the whims of the individual surgeon.

What this abstract really shows is that compliance with the new rule increased, and there were no obvious complications from its use. The other numbers (chest tube insertions, observation failure) are just too subjective to learn much from.

Here are my questions for the presenter and authors:

- Why was there such a large increase in the number of subjects for two identical-length time periods? Both were two years long, yet there were two-thirds more patients in the later period. Did your trauma center volumes go up that much? If not, could this represent some sort of selection bias that might change your numbers?

- You concluded that your new rule decreased the number of “unnecessary” CT scans? How so? It looks like you are using more of them!

- Do you routinely get a chest CT on all your patients with pneumothorax? Seems like a lot of radiation just to decide whether or not to put a tube in.

- How do you manage a pneumothorax found on chest x-ray? Must they get a CT? Or are you willing to watch them and follow with serial x-rays?

- How do you decide to take out the chest tube? Hopefully not another scan!

There should be some very interesting discussion of this abstract!

Reference: THE 35-MM RULE TO GUIDE PNEUMOTHORAX MANAGEMENT: INCREASES APPROPRIATE OBSERVATION AND DECREASES UNNECESARY CHEST TUBES. AAST 2021, Oral abstract #56.