How often have you heard this phrase in a talk or seen it in a journal article:

“Maintain a high index of suspicion”

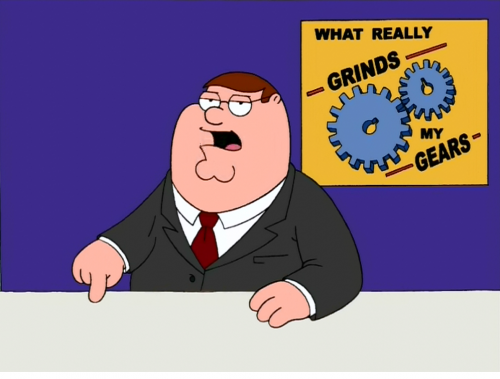

What does this mean??? It’s been popping up in papers and textbooks for at least 30 years. And to me, it’s meaningless. You try to figure out that sentence!

An index is a number, usually mathematically derived in some way. Yet whenever I see or hear this phrase, it doesn’t apply to anything quantifiable. What the author is really referring to is “a high level of suspicion,” not an index.

This term has become a catch-all to caution the reader or listener to think about a (usually) less common diagnostic possibility. As trauma professionals, we are advised to do this about so many things, it really has become sad and meaningless. And don’t we all do this anyway?

Bottom line: Don’t use this phrase in your presentations or writing. It’s silly and doesn’t make any sense. And feel free to chide any of your colleagues who do. Please give us some concrete data so we don’t have to be so suspicious!

Reference: High index of suspicion. Ann Thoracic Surg 64:291-292, 1997.