In my last post, I detailed how to suspect and image a button battery ingestion. In this one, I’ll describe how to extract them, and how quickly it’s necessary.

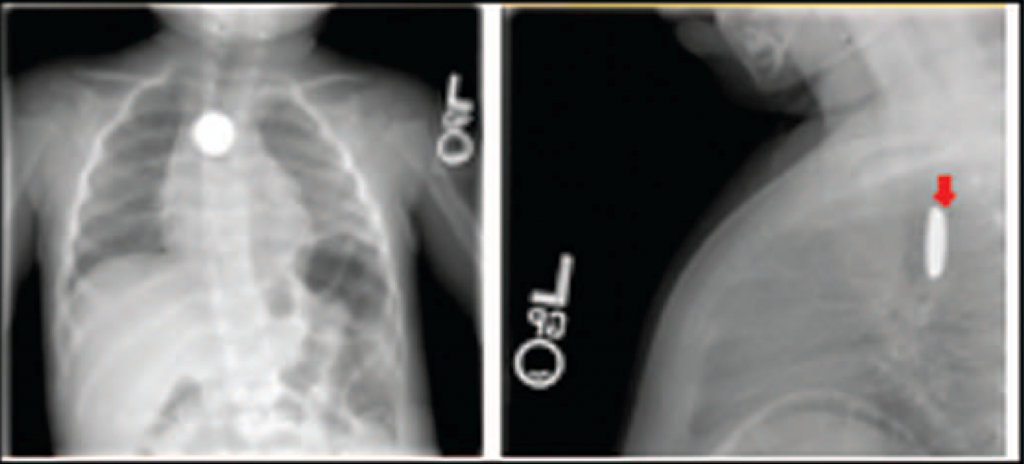

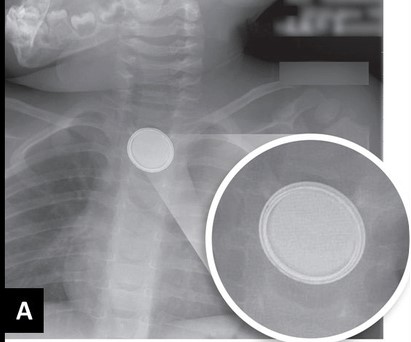

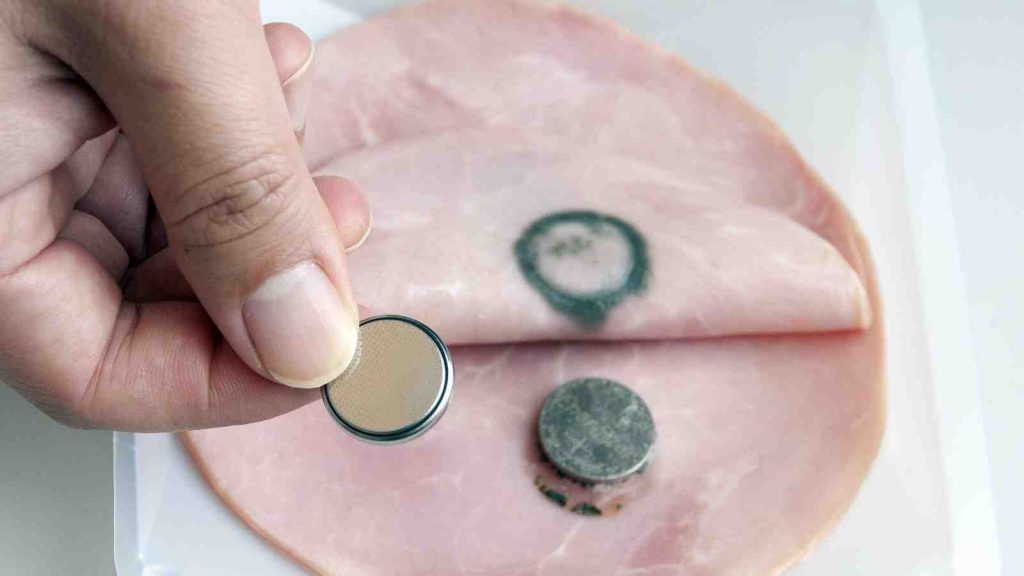

When batteries come to rest and are surrounded by moist mucosal tissue, a current arc is generated around the two sides of the button. This releases heat, which coagulates the surrounding tissue. Depending on the location, closeness of contact, and the duration, these burn injuries may extend into underlying tissue. This is of particular significance in the esophagus, which is in close proximity to the thoracic aorta.

Here’s a simple demonstration you can do at home with some lunch meat:

Here are guidelines for what to do when you encounter pediatric patients who have ingested a button battery:

- If the child is experiencing bleeding from the upper GI tract, activate your trauma team. The child may have an aorto-esophageal fistula. If there is no active bleeding, obtain a chest x-ray to assess the battery’s position. If there is active bleeding, proceed to the OR (preferably a hybrid room if you have one) and use fluoro to locate the battery. If bleeding persists, call appropriate pediatric surgical specialists (surgery, CV surgery, GI), activate your massive transfusion protocol, and consider tamponade with a Blakemore tube (remember those?) or a urinary catheter if you don’t have one.

- No bleeding from the upper GI tract? If the battery is large (>20mm) and/or the child is small (<5 years), and is lodged in the esophagus, proceed immediately to OR and remove endoscopically.

- Batteries in the stomach are of less concern. They will generally pass if <20mm. A repeat x-ray after 48 hours should be obtained for larger batteries. If still in the stomach, they should be removed endoscopically. Smaller batteries will usually pass, and should be re-imaged after two weeks to confirm this.

References:

- Button battery and magnet ingestions in the pediatric patient. Curr Opin Pediatrics 30:653-659, 2018.

- Management of ingested foreign bodies in children: a clinical report of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee. J Pediatric Gastroenterol Nutr 60:562-574, 2015.