The last abstract for the Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons that I will review deals with doing a so-called “pan-scan” for ground level falls. Apparently, patients at this center have been pan-scanned for years, and they wanted to determine if it was appropriate.

This was a retrospective trauma registry review of 9 years worth of ground level falls. Patients were divided into young (18-54 years) and old (55+ years) groups. They were included in the study if they received a pan-scan.

Here are the factoids:

- Hospital admission rates (95%) and ICU admission rates (48%) were the same for young and old

- ISS was a little higher in the older group (9 vs 12)

- Here are the incidence and type of injuries detected:

| Young (n=328) | Old (n=257) | |

| TBI | 35% | 40% |

| C-spine | 2% | 2% |

| Blunt Cereb-vasc inj * | 20% | 31% |

| Pneumothorax | 14% | 15% |

| Abdominal injury | 4% | 2% |

| Mortality * | 3% | 11% |

* = statistically significant

Bottom line: There is an ongoing argument, still, regarding pan-scan vs selective scanning. The pan-scanners argue that the increased risk (much of which is delayed or intangible) is worth the extra information. This study shows that the authors did not find much difference in injury diagnosis in young vs elderly patients, with the exception of blunt cerebrovascular injury.

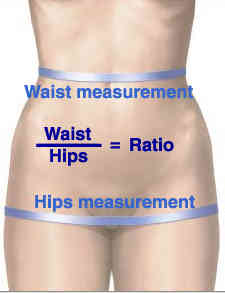

Most elderly patients who fall sustain injuries to the head, spine (all of it), extremities and hips. The torso is largely spared, with the exception of ribs. In my opinion, chest CT is only for identification of aortic injury, which just can’t happen from falling over. Or even down stairs. And solid organ injury is also rare in this group.

Although the future risk from radiation in an elderly patient is probably low, the risk from the IV contrast needed to see the aorta or solid organs is significant in this group. And keep in mind the dangers of screening for a low probability diagnosis. You may find something that prompts invasive and potentially more dangerous investigations of something that may never have caused a problem!

I recommend selective scanning of the head and cervical spine (if not clinically clearable), and selective conventional imaging of any other suspicious areas. If additional detail of the thoracic and/or lumbar spine are needed, specific spine CT imaging should be used without contrast.

Related posts:

Reference: Pan-scanning for ground level falls in the elderly: really? ACS Surgical Forum, trauma abstracts, 2016.