The use of prophylactic antibiotics in patients with facial fractures has been controversial since forever. Some trauma professionals argue that these fractures, many of which involve a sinus or the mouth, should be considered as open fractures.

Several studies on the use of antibiotics prophylactically, preoperatively, and postoperatively have shown a significant amount of variability. A few have shown no benefit from the use of short-, long-, or no antibiotics. In fact, the Surgical Infection Society issued a practice guideline on antibiotic use in facial fractures. Essentially, they recommended that antibiotics not be administered to patients who do not require surgery. And for operative fractures, they recommended against pre- or post-operative antibiotics.

A recently published study examined current practices regarding antibiotic administration, timing, and adverse events. The null hypothesis was that prophylactic antibiotics would not reduce facial fracture-associated infectious complications in nonoperative facial fractures.

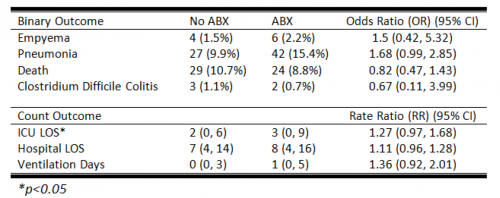

The AAST Facial Fracture Study Group performed a prospective, observational study of adult patients who did not undergo operative repair of their facial fractures. Patients receiving antibiotics for other causes, those who were immunocompromised, and patients with bowel injuries were excluded. The primary outcome was any related infection, drainage, or follow-up visit requiring antibiotics. Secondary outcomes included demographic indicators such as length of stay, ventilator time, discharge disposition, and readmission within 30 days.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 1,835 patients were studied, and two-thirds (64%) did not receive any antibiotics

- Infections developed in 0.7% of patients without antibiotics and 1.7% with

- The vast majority of fractures in all patients (84%) were not considered open (no mucosal exposure)

- Antibiotic administration had a significant association with infectious complications, although the duration of antibiotics did not seem to make a difference

The authors concluded that infection rates were very low despite the majority of patients receiving no antibiotics.

Bottom line: This study provides another set of data points that show us that antibiotics are not necessary in many facial fractures. This is an observational study, so there were wide variations in practice patterns that make the study more difficult to interpret.

There was a relatively small number of patients with “open fractures” that involved exposure to the mucosa. This weakens the study conclusions for this group.

This study joins a growing number that would indicate that nonoperatively managed facial fractures do not require antibiotics. For those that do need surgery, the usual perioperative antibiotic rules still apply.

Reference: Prophylactic antibiotic use in trauma patients with non-operative facial fractures: A prospective AAST multicenter trial. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 98(4):p 557-564, April 2025.