Here’s a 9 minute video demonstrating my easy technique for inserting a chest tube. I’ve included some helpful tips and tricks to make this a quick and easy procedure.

Category Archives: Thorax

Trauma Chest Tube Tips

I’ve written a lot about chest tubes, but there’s actually a lot to know. And a fair amount of misinformation as well. Here’s some info you need to be familiar with:

I’ve written a lot about chest tubes, but there’s actually a lot to know. And a fair amount of misinformation as well. Here’s some info you need to be familiar with:

- Chest trauma generally means there is some blood in the chest. This has some bearing on which size chest tube you choose. Never assume that there is only pneumothorax based on the chest xray. Clot will plug up small tubes.

- Chest tubes for trauma only come in two sizes: big (36Fr) and bigger (40Fr). Only these large sizes have a chance in evacuating most of the clot from the pleural space. The only time you should consider a smaller tube, or a pigtail type catheter, is if you know for a fact that there is no blood in the chest. The only way to tell this is with chest CT, which you should not be getting for diagnosis of ordinary chest trauma. Having said this, there is some more recent literature that suggests that size might not matter as much as we think.

- When inserting the tube, you have no control of the location the tube goes once you release the instrument used to place it. Some people believe they can direct a tube anteriorly, posteriorly, or anywhere they want. They can’t, and it’s not important (see next tip).

- Specific tube placement is not important, as long as it goes in the pleural space. Some believe that posterior placement is best for hemothorax, and anterior placement for pneumothorax. It doesn’t really matter because the laws of physics make sure that everything gets sucked out of the chest regardless of position except for things too big to fit in the tube (e.g. the lung).

- Tunneling the tube tract over a rib is not necessary in most people. In general, we have enough fat on our chest to ensure that the tract will close up immediately when the tube is pulled. A nicely placed dressing is your insurance policy.

- Adhere to an organized tube management protocol to reduce complications and the time the tube is in the chest.

And finally, amaze your friends! The French system used to size chest tubes is the diameter of the tube in millimeters times three (3.14159, pi to be exact). So a 40Fr chest tube has a diameter of 13.3mm.

Coming This Week: Chest Tube Week

I’m dedicating the coming fortnight (that’s two weeks to you non-Brits) to the lowly chest tube. It’s taken for granted, but there is a lot a variability on how we insert, manage, and pull out these devices. Here’s what’s coming, starting tomorrow:

- Videos on how to insert a chest tube and pigtail catheter

- A video on how to pull a chest tube properly

- Chest tube tips and tricks

- A practice guideline for chest tube management

- Troubleshooting chest tubes

- Collection systems gone bad

- Lateral chest x-ray for pneumothorax: waste of time?

- When to remove a chest tube

- Autotransfusing blood from the collection system

If you want email reminders every day when a post goes live, just click here to subscribe!

Retained Hemothorax Part 4: The Practice Guideline

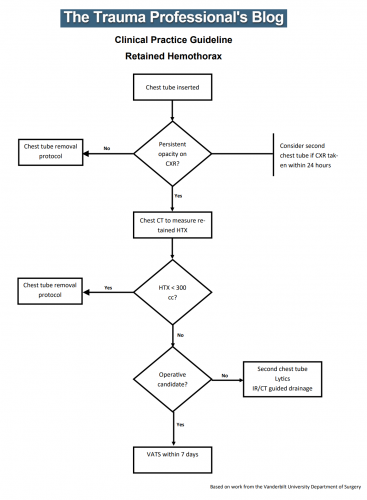

Over the last three days, I reviewed some data on lytics at the request of some of my readers. Then I looked at a paper describing one institution’s experience dealing with retained hemothorax, including the use of VATS. But there really isn’t much out there on how to roll all this together.

Until now. The trauma group at Vanderbilt has a paper in press describing their experience with a home-grown practice guideline for managing retained hemothorax. Here’s what it looks like:

I know it’s small, so just click it to download a pdf copy. I’ve simplified the flow a little as well.

All stable patients with hemothorax admitted to the trauma service were included over a 2.5 year period. The practice guideline was implemented midway through this study period. Before implementation, patients were treated at the discretion of the surgeon. Afterwards, the practice guideline was followed.

Here are the factoids:

- There were an equal number of patients pre- and post-guideline implementation (326 vs 316)

- An equal proportion of each group required an initial intervention, generally a chest tube (69% vs 65%)

- The number of patients requiring an additional intervention (chest tube, VATS, lytics, etc) decreased significantly from 15% to 9%

- Empyema rate was unchanged at 2.5%

- Use of VATS decreased significantly from 8% to 3%

- Use of catheter guided drainage increased significantly from 0.6% to 3%

- Hospital length of stay was the same, ranging from 4 to 11 days (much shorter than the lytics studies!)

Bottom line: This is how design of practice guidelines is supposed to work. Identify a problem, typically a clinical issue with a large amount of provider care variability. Look at the literature. In general, find it of little help. Design a practical guideline that covers the major issues. Implement, monitor, and analyze. Tweak as necessary based on lessons learned. If you wait for the definitive study to guide you, you’ll be waiting for a long time.

This study did not significantly change outcomes like hospital stay or complications. But it did decrease the number of more invasive procedures and decreased variability of care, with the attendant benefits from both of these. It also dictates more selective (and intelligent) use of additional tubes, catheters, and lytics.

I like this so much that I plan to adopt it at my center!

Download the practice guideline here.

Related posts:

- Why create practice guidelines?

- How to craft a practice guideline

- Reinventing the practice guideline wheel

Posts in this series:

Reference: Use of an evidence-based algorithm for patients with traumatic hemothorax reduces need for additional interventions. J Trauma, in press, December 14, 2016.

Retained Hemothorax Part 3: VATS

I’ve written about the use of lytics to treat retained hemothorax over the past few days. Although it sounds like a good idea, we just don’t know that it works very well. And they certainly don’t work fast. Lengths of stay were on the order of two weeks in both studies reviewed.

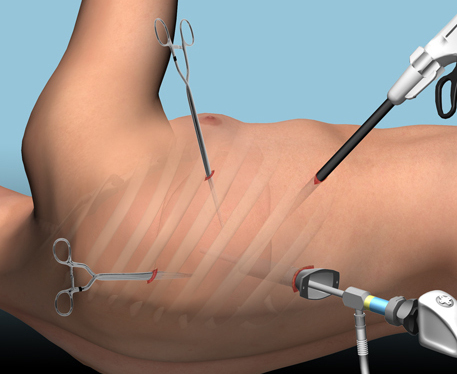

The alternative is video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). So let’s take a look at what we know about it. This procedure is basically laparoscopy of the chest. A camera is inserted, and other ports are added to allow insertion of instruments to suck, peel, and scrape out the hemothorax.

A prospective, multi-center study was performed over a 2 year period starting in 2009. Twenty centers participated, contributing data on 328 patients with retained hemothorax. This was defined as CT confirmation of retained blood and clot after chest tube placement, with evidence of pleural thickening.

Here are the factoids:

- 41% of patients had antibiotics given for chest tube placement (this is interesting given the lack of consensus regarding their effectiveness!)

- A third of patients were initially managed with observation, and most of them (82%) did not need any further procedures (83 of 101 patients)

- Observation was more successful in patients who were older, had smaller hemothoraces (<300cc), smaller chest tubes (!!, <34 Fr), blunt trauma, and peri-procedure antibiotics (?)

- An additional chest tube was inserted in 19% of patients, image guided drain placement in 5%, and lytics in 5%. Half to two-thirds of these patients required additional management.

- VATS was used in 34% of patients. One third of them required additional management including another chest tube, another VATS, or even thoracotomy.

- Thoracotomy was most likely required if there was a diaphragm injury or large hemothorax (<900cc)

- Empyema and pneumonia were common (27% and 20%, respectively)

Bottom line: There’s a lot of data in this paper. Most notably, many patients resolve their hemothorax without any additional management. But if they don’t, additional tubes, guided drain placement, and lytics work only a third of the time and contribute to additional time in the hospital. Even VATS and thoracotomy require additional maneuvers 20-30% of the time. And infectious complications are common. This is a tough problem!

Tomorrow, I’ll try to roll it all together and suggest an algorithm to try to optimize both outcomes and cost.

Posts in this series:

Reference: Management of post-traumatic retained hemothorax: A prospective, observational, multicenter AAST study. 72(1):11-24, 2012.