For most places, including Minnesota, hypothermia time is just about over! However, this trauma problem can occur nearly anywhere and at any time. And especially during a massive resuscitation. The optimal way to warm paitients has been debated for years. A number of very interesting techniques have been devised. Ever wonder how fast / effective they are?

I’ve culled data from a number of sources, and here is a summary what I found. And of course, the disclaimer: “your results may vary.”

| Warming Technique | Rate of Rewarming |

| Passive external (blankets, lights) | 0.5° C / hr |

| Active external (lights, hot water bottle) | 1 – 3° C / hr |

| Bair Hugger (a 3M product, made in Minnesota of course!) | 2.4° C / hr |

| Hot inspired air in ET tube | 1° C / hr |

| Fluid warmer | 2 – 3° C / hr |

| GI tract irrigation (stomach or colon, 40° C fluid, instill for 10 minutes, then evacuate) | 1.5 -3° C / hr |

| Peritoneal lavage (instill for 20-30 minutes) | 1 – 3° C / hr |

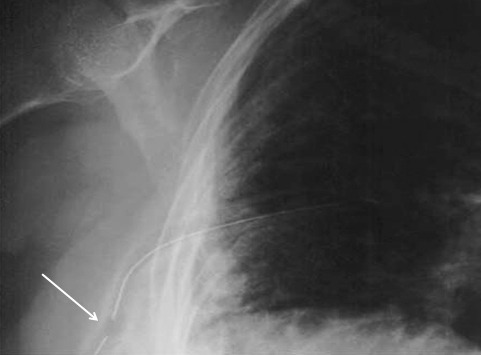

| Thoracic lavage (2 chest tubes, continuous flow) | 3° C / hr |

| Continuous veno-venous rewarming | 3° C / hr |

| Continuous arterio-venous rewarming | 4.5° C / hr |

| Mediastinal lavage (thoracotomy) | 8° C / hr |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass | 9° C / hr |

| Warm water immersion (Hubbard or therapy tank) | 20° C / hr |