The management of blunt spleen injury has evolved significant over the time I’ve been in practice. Initially, the usual formula was:

Spleen injury = splenectomy

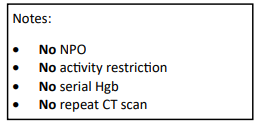

This began to change in the late 1980’s, and beginning in the early 90’s nonoperative management became the rage. We spent the next 10-15 years tweaking the details, gradually reducing bed rest and NPO times, and increasing the success rate through smart patient selection and discovering new adjuncts.

One of these adjuncts was angiography with embolization. The ShockTrauma Center in Maryland was an early adopter and protocolized its use in patients with high-grade injuries.

But now, they are questioning the utility of this tool in certain patients: those with splenic pseudoaneurysms (PSA). They theorized that modern, high resolution CT identifies relatively unimportant pseudoaneurysms. They conducted a 5-year retrospective review of their experience.

Here are the factoids:

- They identified 717 splenic injuries, of whom 155 were embolized but only 140 patients had adequate records and imaging for review

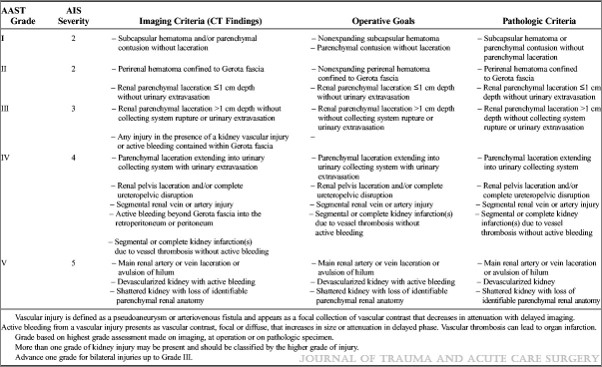

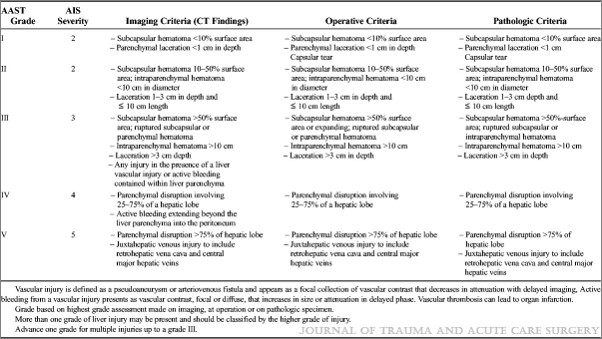

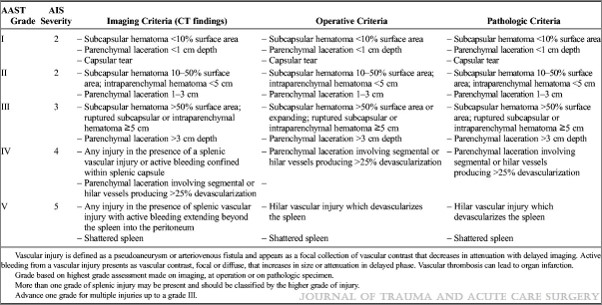

- The majority of patients had high grade injury: 31% Grade 3, 61% Grade 4, 1% Grade 5

- Extravasation was seen in 17% and PSA in 52%

- About 44% of patients went to angiography within 6 hours, but the mean was 17 hours indicating quite a few outliers

- Among the 73 patients with an initial PSA , a third of them did not have a detectable lesion during angiography

- Patients who underwent embolization for PSA had a followup CT 48-72 hours afterwards, persistently perfused PSA were seen in 40% (!)

- No patients with PSA who were only observed required delayed splenectomy

The authors conclude that a third of pseudoaneurysms may be clinically insignificant, and that 40% of them persist after embolization. They do not, however, offer any recommendations based on their data.

Here are my comments: This is an interesting study. My read of the abstract and slides would indicate that this group routinely sends all Grade 3 and 4 injuries to angio, and Grade 5 could go to either angio or OR. They take their good time going to interventional radiology (mean 17 hours from arrival), and get a routine followup CT 48-72 hours from hitting the door if they didn’t go to the OR.

If I were to play the devil’s advocate, I might think that interventional radiology was being de-emphasized for some reason. Was there some reluctance to send patients there, or limited availability? This might explain the long access times. And how are the radiologists not shutting down 40% of PSA that are seen?

I am intrigued by the study, but there are a lot more details needed to get some good takeaways from it.

Here are my questions for the presenter and authors:

- Please explain why it takes so long to send patients to angiography. Less than half got there in less than 6 hours, and the mean of 17 hours means that many didn’t get there until the next day.

- Does this small study have the statistical power to say that some PSA are benign? The groups are very small, and I would speculate that the group size needed to show significance is in the high hundreds.

- What was the reason for splenectomy in the 2 patients who underwent embolization? Was it related to the pseudoaneurysm or something else?

- How can you be sure that these PSA are insignificant? Frequently, pseudoaneurysms don’t explode for 7-10 days. Do you have any data on patients who returned to a hospital with delayed bleeding?

- If you believe that many pseudoaneurysms are benign, how do you propose to manage the patients? Observe until they explode? Repeat a contrast CT scan, with the associated contrast and radiation re-dose? And how long would you wait to do this? What would your new protocol be?

I’ll be all ears on Friday when this abstract is presented live.