Every trauma center needs a massive transfusion protocol (MTP). It automates the preparation and delivery of critical blood products in seriously injured patients. Unfortunately, there are many moving parts, so numerous things can go wrong.

This series of posts will break down the entire MTP process, step by step. Although it is designed for centers developing their first MTP, it also provides valuable information for established centers that want to tweak and optimize theirs. I’ll start today with tips on how to build a solid MTP at your center.

Your massive transfusion protocol is a complex set of processes that touch many, many areas within your hospital. There are five basic components (and a few sub-components) to any MTP, so let’s dig into them one by one. They are:

- Universality

- Activation

- Logistics

- Components

- Runners

- Documentation

- Coolers

- Deactivation

- Analysis

Let’s scrutinize each one, starting with the first two today.

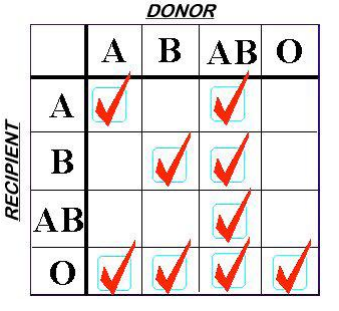

Universality. This means that there should be one, and only one MTP in your hospital. I’ve seen some hospitals that have one MTP for trauma, one for cardiothoracic surgery, one for OB, one for GI, and on and on. Yes, each of those services deals with patients who are suffering from blood loss. But it’s the same blood that your trauma patients lose! There’s no need to create a protocol for each, with different ratios, extra drugs, etc. This can and will create confusion in the blood bank which may lead to serious errors.

Activation. This consists of two parts: how do we decide to activate, and then how does everyone involved find out that the MTP is actually being activated? I’ll discuss activation criteria later in the series. But what about the notification process? Phone call? Order in the electronic medical record (EMR)? Smoke signals?

The most reliable method is a good, old-fashioned phone call. Do not use your EMR except for documentation purposes. Unless there is a very reliable system in the blood bank that translates an EMR order into an annoying alarm or flashing lights, don’t rely on this at all.

Then decide upon the minimum amount of information that the blood bank needs to begin preparing blood products. This usually consists of a name or temporary patient identifier, sex, and location of activation. Ensure that an ID or transfusion band is affixed to the patient so that wrong blood products are not given in multiple patient events.

In my next post, I’ll continue with the logistics of the MTP.