IO lines are a godsend when we are faced with a patient who desperately needs access but has no veins. The tibia is generally easy to locate and the landmarks for insertion are straightforward. They are so easy to insert and use, we sometimes “set it and forget it”, in the words of infomercial guru Ron Popeil.

But complications are possible. The most common is an insertion “miss”, where the fluid then infuses into the knee joint or soft tissues of the leg. Problems can also arise when the tibia is fractured, leading to leakage into the soft tissues. Infection is extremely rare.

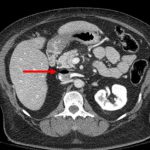

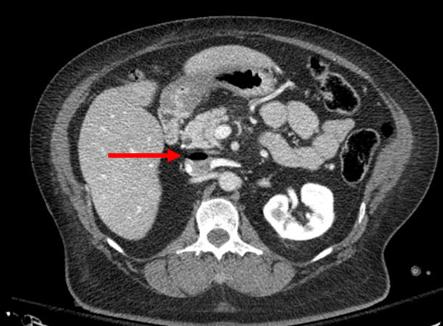

This photo shows the inferior vena cava of a patient with bilateral IO line insertions (black bubble at the top of the round IVC).

During transport, one line was inadvertently disconnected and probably entrained some air. There was no adverse clinical effect, but if the problem is not recognized and the line is not closed properly, there could be.

Bottom line: Treat an IO line as carefully as you would a regular IV. You can give anything through it that can be given via a regular IV: crystalloid, blood, drugs. And even air, so be careful!