I just finished reading a recent paper published in the Journal of Trauma that purports to examine individual surgeon outcomes after trauma laparotomy. The paper was presented at AAST last year, and is authored by the esteemed trauma group at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. It was also recently discussed in the trauma literature review series that is emailed to members of EAST regularly.

Everyone seems to be giving this paper a pass. I won’t be so easy on it. Let me provide some detail.

The authors observe that the mortality in patients presenting in shock that require emergent laparotomy averages more than 40%, and hasn’t changed significantly in at least 20 years. They also note that this mortality varies widely from 11-46%, and therefore “significant differences must exist at the level of the individual surgeon.” They go on to point out that damage control usage varies between individuals and trauma centers which could lead to the same conclusion.

So the authors designed a retrospective cohort study of results from their hospital to try to look at the impact of individual surgeon performance on survival.

Here are the factoids:

- Over the 15 month study period, there were over 7,000 trauma activations and 252 emergent laparotomy for hemorrhage control

- There were 13 different trauma surgeons and the number of laparotomies for each ranged from 7 to 31, with a median of 15

- There were no differences in [crude, in my opinion] patient demographics, hemodynamics, or lab values preop

- “Significant” differences in management and outcomes between surgeons were noted:

- Median total OR time was significantly different, ranging from 120-197 minutes

- Median operation time was also different, from 75-151 minutes across the cohort of surgeons

- Some of the surgeons had a higher proportion of patients with ED LOS < 60 minutes and OR time < 120 minutes

- Resuscitation with red cells and plasma varied “significantly” across the surgeons

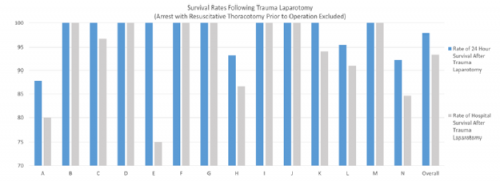

- Mortality rates “varied significantly” across surgeons at all time points (24-hour, and hospital stay)

- There were no mortality differences based on surgeons’ volume of cases, age, or experience level

The authors acknowledged several limitations, included the study’s retrospective and single-center nature, the limited number of patients, and its limited scope. Yet despite this, they concluded that the study “suggests that differences between individual surgeons appear to affect patient care.” They urge surgeons to openly and honestly evaluated ourselves. And of course, they recommend a large, prospective, multicenter study to further develop this idea.

Bottom line: This study is an example of a good idea gone astray. Although the authors tried to find a way to stratify patient injury (using ISS and individual AIS scores and presence of specific injuries) and intervention times (time in ED, time to OR, time in OR, op time), these variables just don’t cut it. They are just too crude. The ability to meaningfully compare these number across surgeons is also severely limited by low patient numbers.

The authors found fancy statistical ways to demonstrate a significant difference. But upon closer inspection, many of these differences are not meaningful clinically. Here are some examples:

- Intraoperative FFP ranged from 0-7 units between surgeons, with a p value of 0.03

- Postoperative FFP ranged from 0-7 units, with a p value of 0.01

- Intraoperative RBC usage was 0-6 units with the exception of one surgeon who used 15 in a case, resulting in a p value of 0.04

The claim that mortality rates varied significantly is difficult to understand. Overall p values were > 0.05, but they singled out one surgeon who had a significant difference from the rest in 22 of 25 mortality parameters listed. This surgeon also had the second highest patient volume, at 25.

The authors are claiming that they are able to detect significant variations in surgeon performance which impacts timing, resuscitation, and mortality. I don’t buy it! They believe that they are able to accurately standardize these patients using simple demographic and performance variables. Unfortunately, the variables selected are far too crude to accurately describe what is wrong inside the patient and what the surgeon will have to do to fix it.

Think about your last 10 trauma laparotomies where your patient was truly bleeding to death. How similar were they? Is there no difference between a patient with a mesenteric laceration with bleeding, an injury near the confluence of the superior mesenteric vessels, and a right hepatic vein injury? Of course there is. And this will definitely affect the parameters measured here and crude outcomes. Then add some unfavorable patient variables like obesity or previous laparotomy.

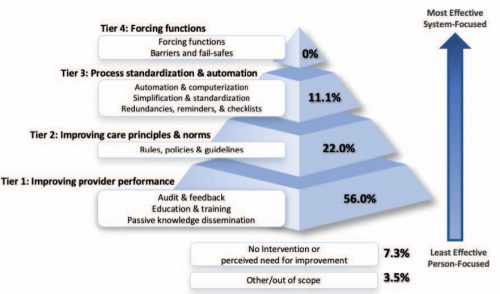

In my estimation, this paper completely misses the point because it’s not possible to retrospectively categorize all the possible variables impacting “surgeon performance.” This is particularly true of the patient variables that could not possibly be captured. The only way to do this right is to analyze each case as prospectively as possible, as close to the time of the procedure and as honestly as possible. And this is exactly what a good trauma M&M process does!

So forget the strained attempts at achieving statistical significance. Individual surgeon performance and variability will come to light at a proper morbidity and mortality conference, and should be evened out using the peer review and mentoring process. It’s not time to start blaming the surgeon!

Reference: It is time to look in the mirror: Individual surgeon outcomes after emergent trauma laparotomy. J Trauma 92(5):769-780, 2022.