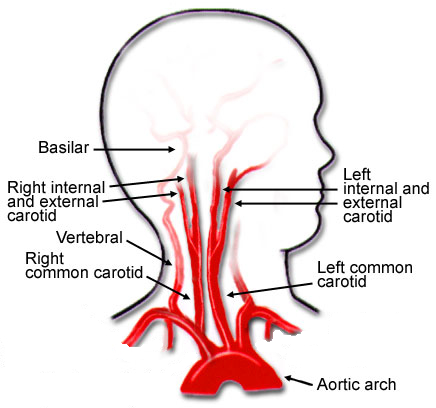

In my last post, I described how common we think blunt carotid and vertebral injury (BCVI) really is. Today, I’ll review how we screen for this condition.

Currently, there are three systems in use: Denver, Expanded Denver, and Modified Memphis. Let’s look at each in detail.

Denver BCVI Screening

There is an original Denver screening system, and a more recent modification. The original system was divided into mechanism, physical signs, and radiographic findings. It was rather rudimentary and evolved into the following which uses both signs and symptoms, and high-risk factors.

Signs and symptoms

- potential arterial hemorrhage from the neck, nose, or mouth

- cervical bruit in patients <50 years of age

- expanding cervical hematoma

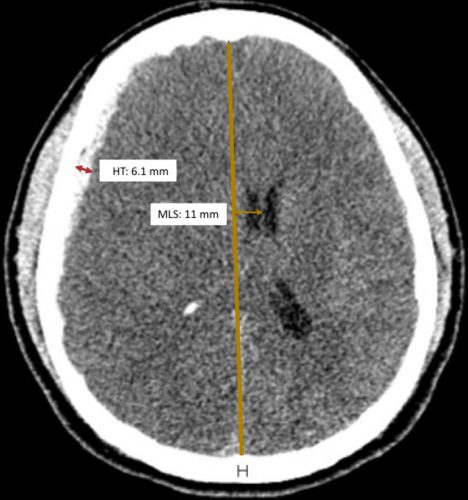

- focal neurologic deficit (transient ischemic attack, hemiparesis, vertebrobasilar symptoms, Horner syndrome) incongruous with head CT findings

- stroke on CT

Risk factors

- Le Fort II or III mid-face fractures

- Cervical spine fractures (including subluxations), especially fractures involving transverse foramen or C1-C3 Vertebrae

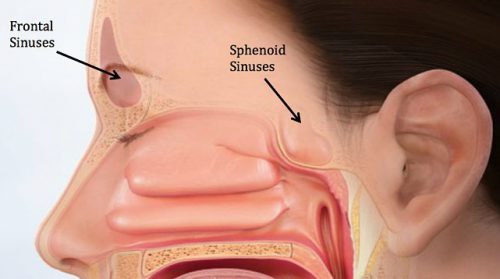

- Basilar skull fracture and involvement of carotid canal

- Diffuse axonal injury with GCS <8

- Near hanging with anoxic brain injury

- Seat belt sign (or other soft tissue neck injury) especially if significant associated swelling or altered level of consciousness

The Denver group reviewed their criteria in 2012 and found that 20% of the patients who had identified BCVI did not meet any of their criteria. And obviously, this number cannot include those who were never symptomatic and therefore never discovered.

Based on their analysis, they added several additional risk factors to the original system:

- Mandible fracture

- Complex skull fracture/basilar skull fracture/occipital condyle fracture

- TBI with thoracic injuries

- Scalp degloving

- Thoracic vascular injuries

- Blunt cardiac rupture

The downside of these modifications is that they are a little more complicated to identify. The original criteria were fairly straightforward yes/no items. But “TBI with thoracic injuries?” Both the TBI part and the thoracic injury part are very vague. This modification casts a wider net for BCVI, but the holes in the net are much larger.

Memphis BCVI Screening

Let’s move on to the modified Memphis system for identifying BCVI. It consists of seven findings that overlap significantly with the Denver criteria. The underlined phrases indicated the modifications that were applied to the original criteria.

- base of skull fracture with involvement of the carotid canal

- base of skull fracture with involvement of petrous temporal bone

- cervical spine fracture (including subluxation, transverse foramen involvement, and upper cervical spine fracture)

- neurological exam findings not explained by neuroimaging

- Horner syndrome

- Le Fort II or III fracture pattern

- neck soft tissue injury (e.g. seatbelt sign, hanging, hematoma)

Interestingly, these modifications were first described in an abstract which was never published as a paper. Yet somehow, they stuck with us.

So there are now two or three possible systems to choose from when deciding to screen your blunt trauma patient. Which one is best?

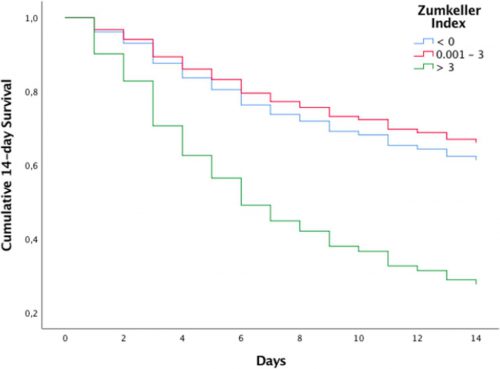

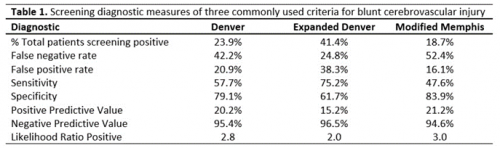

Let’s go back to the AAST abstract presented by the Birmingham group this year that I mentioned previously. Not only did they determine a more accurate incidence, but they also tested the three major screening systems to see how each fared. See Table 1.

Look at these numbers closely. When any of these systems were applied and the screen was negative, the actual percentage of patients who still actually had the injury ranged from about 25% to 50%! Basically, it was a coin toss with the exception of the Expanded Denver criteria performing a little better.

If you are a patient and you actually have the injury, how often does any screening system pick it up? Oh, about one in five times. Again, this is not what we want to see.

So what to do? The Expanded Denver screen has a lower false negative rate, but the total number of positive screens, and hence the number of studies performed, doubles when it is used.

Here’s how I think about it. BCVI is more common than we thought in major blunt trauma. If not identified, a catastrophic stroke may occur. Current screening systems successfully flag only 50% of patients for imaging. So in my opinion, we need to consider imaging every patient who is already slated to receive a head and cervical spine CT after major blunt trauma! At least until we have a more selective (and reliable) set of screening criteria.

References:

- (Denver) Optimizing screening for blunt cerebrovascular injuries. Am J Surg. 1999;178:517–522.

- (Expanded Denver) Blunt cerebrovascular injuries: Redefining screening criteria in the era of noninvasive diagnosis. J Trauma 2012;72(2):330-337.

- (Memphis) Prospective screening for blunt cerebrovascular injuries: analysis of diagnostic modalities and outcomes. Ann Surg. 2002, 236 (3): 386-393.

- (Modified Memphis) Diagnosis of carotid and vertebral artery injury in major trauma with head injury. Crit care. 2010;14(supp1):S100.