We consult our neurosurgeons too often. Think back on all the head injured patients you have admitted and placed a neurosurgical consult. How many times did they recommend something new or different, or take them to surgery? Not very often, I would guess.

This is becoming a hot topic. Check out the references below to read about a few other studies that have taken a similar approach.

The trauma group at Scripps Mercy in San Diego retrospectively reviewed their admissions to determine how often patients with mild TBI (GCS > 13) and some degree intracranial hemorrhage required neurosurgical intervention, even if they were intoxicated or taking anti-platelet or anticoagulant drugs. A total of 500 patients were studied over a 28 month period.

Here are the factoids:

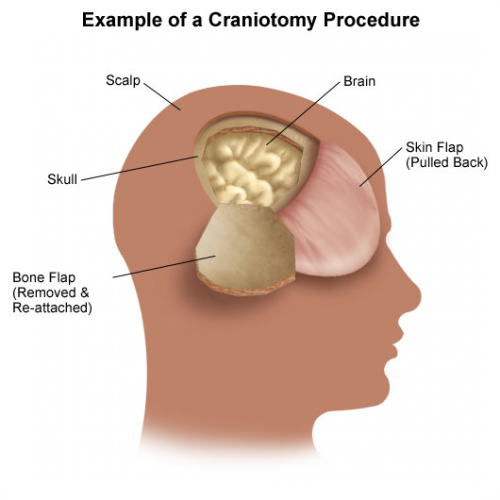

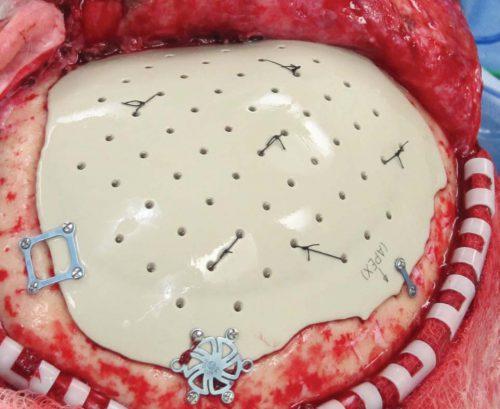

- 49 (10%) of patients required some sort of neurosurgical intervention (41 craniotomy/craniectomy, 8 ICP monitors)

- 93% of patients had neurosurgical consultation, and made additional recommendations in only 10 (2%),none of which changed management

- There was no clinical difference in GCS between those who received an intervention and those who did not

- Epidural and subdural hematomas were significant predictors of neurosurgical intervention

- Intoxication or use of anti-platelet or anticoagulant drugs was not associated with intervention. These were present in 30% of all patients!

- Unsurprisingly, ICU and hospital length of stay were longer in patient who underwent an intervention

Bottom line: As I said, this seems to be a hot research topic. And in this study, the numbers are getting larger and the criteria more inclusive (alcohol and anticoagulants allowed).

Neurosurgeons play a very important role in patients with more moderate to injury to their brain, and with spine injuries. But their input may not be needed in many patients with milder injuries. These data suggest that, in patients with GCS > 13, only subdural and epidural hematomas require consultation because they are much more likely to require intervention.

This parallels a practice guideline we have in place where patients with subarachnoid or small intraparenchymal hemorrhage, or a linear skull fracture are managed by the trauma service without neurosurgical consultation. We do involve them if there is any intracranial hemorrhage with a history of anticoagulant use, however.

We all need to use our neurosurgeons wisely, and this paper helps to clarify situations where they may and may not be needed.

Related posts:

- Subarachnoid/ICH/Skull fracture protocol without neurosurgery

- Similar study without anticoagulants

- And another smaller study

Reference: Routine neurosurgical consultation is not necessary in mild blunt traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 82(4):776-780, 2017