I’ve previously blogged about the flat vena cava sign as an indicator of low volume status in trauma patients. And I commented on this paper when it was presented at EAST, which had a surprisingly negative result. It’s now been vetted by peer reviewers and published, and I’ve had the opportunity to read through the entire manuscript (always important). So let’s take a second look now.

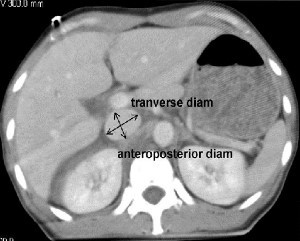

A retrospective study at George Washington University was carried out over a one year period. They looked at all of their highest level trauma activation patients who also underwent CT scan of the abdomen. Images were read by three radiologists and inter-rater reliability was reviewed. The transverse to anteroposterior diameter ratios were calculated to determine flatness.

Here are the factoids:

- 276 patients met enrollment criteria, and were mostly male and blunt trauma

- The IVC was nearly round in 21% of patients and collapsed in 26%

- There was no association between IVC shape and shock index, blood pressure, Hbg, lactate, urgent operation, angiography or length of stay

- There was also no association between IVC shape and blood transfusion or death

- Correlation of the reads between radiologists was good

So what gives? A paper I reviewed three years ago in the Journal of Trauma came to a different conclusion. They found that a flat IVC on CT scan (defined as a transverse to AP ratio of 4:1 or greater) was associated with a significantly higher chance of receiving more crystalloid or blood, as well as requiring an operation within 24 hours.

This newer paper was able to look at a larger group of patients, and they were able to tease out why it initially looked like the flat cava looked like a good predictor for bad things to come. The problem was statistical skewing from a few extreme outliers. When properly corrected, it completely changed things. And looking at the older study, it appears that outliers may have also been the reason for the positive result. This is why I encourage everyone to always read the entire paper! The older paper involved a smaller series (114 patients), but it was prospective and seemed to have reasonable statistical analyses.

Bottom line: It looks like the flat vena cava sign, as measured by a static CT, should be discarded as an indicator of impending shock. Whether or not a more dynamic look (using ultrasound) is valuable remains to be determined.

Related post:

Reference: Inferior vena cava size is not associated with shock following injury. J Trauma 77(1):34-39, 2014.