Is it real, or just another one of those crazy things that radiologists like to add to their reports? I recently came across one of these for the first time in over 30 years of practice. What is it? And is it significant in your management of a trauma patient?

A rudimentary rib is simply an extra one (supernumerary). They can be found on vertebrae where ribs are not supposed to be present, typically C7 and L1. The most common supernumerary ribs are found at C7, and are a well documented cause of thoracic outlet syndrome.

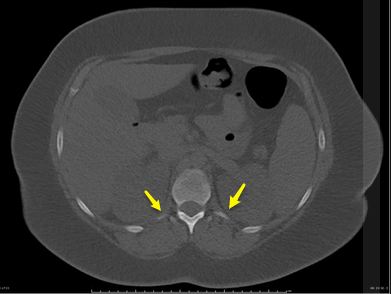

Rudimentary ribs are less commonly found on lumbar vertebrae, and they tend to be longer than the transverse processes. This means that it is possible to break them given moderate to high energy blunt torso trauma. The image below shows a person with 2 rudimentary lumbar ribs on L1.

These are very rare congenital variants. It is more likely that your patient is showing abnormal bone formation after a previous fracture, so question them closely for a history of trauma.

What’s the clinical significance? There’s little chance of hemothorax or pneumothorax. But they cause pain like any other fracture. Just apply your usual routine for rib fracture management: analgesia and pulmonary toilet. Since it takes a relatively large amount of energy to break these short little ribs, be on the lookout for other occult injuries as well.

Bottom line: This isn’t just a weird radiology “red herring.” Rudimentary rib fractures can occur, although a history of previous injury should be ruled out. Manage like any other rib fracture, but beware of potential occult injuries.

Related posts: