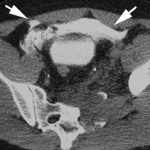

Extraperitoneal Bladder Rupture

This injury is likely to occur in patients who have a full bladder and sustain anterior pelvic trauma that typically leads to fractures. They generally present with gross hematuria upon placement of the bladder catheter. This should prompt an abdominal CT scan with cystogram technique.

CT cystogram involves pressurizing the bladder with contrast prior to the study. This differs from the usual method of clamping the catheter and allowing the bladder to passively fill. The literature here is clear: failure to use cysto technique will miss 50% of these injuries.

The majority of extraperitoneal bladder injuries can be treated nonoperatively, and probably do not need Urology involvement. The bladder catheter is left in place 10-14 days (we do 10 days), and a repeat cystogram is obtained. If there is no leak, the catheter can be removed. If there is still some leakage, Urology consultation should then be obtained.

There are a few cases where operative management is required:

- There is some intraperitoneal component of bladder injury

- Fixation of the pubic rami is required (bathing the orthopedic hardware with urine is frowned upon)

- Failure of conservative management

Arrows in the photo show extraperitoneal extravasation of cystogram contrast.

Related posts: