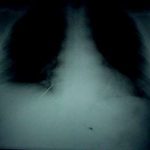

Typical order: “chest CT with and without contrast”

A review of Medicare claims from 2008 showed that 5.4% of patients received double CT scans of the chest. Although the median was about 2% across 3,094 hospitals, 618 hospitals performed double scans on more than 10% of their patients. And 94 did it on more that half! One of the outliers was a small hospital in Michigan that double scanned 89% of Medicare patients! As expected, there was wide variation from hospital to hospital, and from region to region around the US.

Time for some editorial comment.

This practice is very outdated and shows a lack of understanding of the information provided by CT. Furthermore, it demonstrates a lack of concern for radiation exposure by both the ordering physician and the radiologist, who should know better.

Some officials at hospitals that had high scan rates related that radiologists ordered or okayed the extra scan because they believed that “more information was better.” There are two problems with this thinking.

- Information for information’s sake is worthless. It is only important if it changes decision making and ultimately makes a difference in outcome.

- As with every test we do, there may be false positives. But we don’t know they are false, so we investigate with other tests, most of which have known complications.

The solution is to do only what is clinically necessary and safe. The tests ordered should be based on the best evidence available, which demands familiarity with current literature.

In trauma, there are a few instances where repeat scanning of an area is required. Examples include solid organ lesions which may represent an injury or a hemangioma, and CT cystogram to exclude bladder trauma. In both cases, only a selected area needs to be re-scanned, not the entire torso.

Bottom line: Physicians and hospitals need to take the lead and rapidly adopt or develop guidelines which are literature-based. State or national benchmarking is essential so that we do not continue to jeopardize our patient’s safety and drive up health care costs.

Tomorrow I’ll share the blunt trauma imaging protocol we use which has decreased trauma CT use significantly at Regions Hospital.

Related posts: