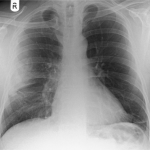

Pulmonary Contusion After Sports Injury

Most pulmonary contusions occur after diffuse, high energy blunt trauma like a fall or car crash. Occasionally, pulmonary injury can occur after a much more focal injury like an impact during sports. This may occur due to direct impact from another player, or from a rapidly moving object like a ball or puck. Today, I’ll focus on the latter, impact from a fast-moving object.

Typically, the athlete will complain of pain at the area of impact and some degree of breathing impairment. This is usually due to musculoskeletal pain, rib fracture or involuntary splinting. It is possible to develop pneumothorax or hemothorax, especially if a rib is fractured. At some point, hemoptysis may be present. This is pathognomonic for the presence of a pulmonary contusion.

Any athlete with more than mild to moderate pain, or any physical exam findings other than tenderness, should be more fully evaluated. Here are some important tips:

- The only imaging required is a two view conventional chest xray. This will identify significant pneumothorax, hemothorax or contusions that require additional management.

- Chest CT is not indicated. It does not change management.

- Use your typical algorithms for managing hemothorax and pneumothorax

- A pneumatocele visible on the xray indicates a small pulmonary laceration. A followup xray or two may be needed to ensure that it does not expand or cause a pneumothorax. Thoracic surgery involvement is not usually indicated

- Hemoptysis is normal, and may present immediately or several days later. The patient should be reassured in advance so they don’t call you frantically in the middle of the night.

Image source: internet