Previous studies have shown that higher hospital costs are associated with longer length of stay (LOS). This makes sense, because the longer a patient stays in the hospital, the more that is “done” for them, and more daily charges are incurred. Obvious savings can occur if we look globally at services, medications, etc while the patient is in the hospital.

But does the admission service make a difference in LOS or cost? It shouldn’t if care is fairly uniform. A group of orthopedic surgeons at Vanderbilt in Nashville looked at a large group of isolated hip fracture patients (n=614) to see if LOS (used as a surrogate for cost) was significantly different. They also tried to control for a host of factors that could affect time in the hospital between the two groups.

Here are the factoids:

- About half of the patients were admitted to the orthopedics service, and half to medicine

- Median length of stay was way different! 4.5 days on Ortho vs 7 days on Medicine

- Readmission rates were also significantly higher on Medicine, 30% vs 23%

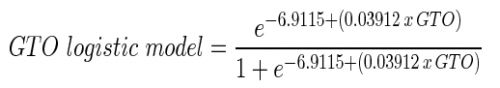

- After controlling for factors such as medical comorbidities, age, smoking and alcohol, ASA score, obesity, and others, a regression model showed that patients were still likely to stay about 50% longer if admitted to a medicine service.

Bottom line: Obviously, this is the experience of a single institution. But the difference in length of stay, and hence costs, was striking. As the US moves toward a bundled payment system, this will become a major problem. The initial LOS is more costly on the medicine service, and readmission for the same problem will not be reimbursed. Why the difference? Coordination of care between two services? Lack of familiarity with surgical nuances? This study did not look at that.

But it does point out the need to more closely integrate the care of the elderly in particular, and patients with a broad range of needs in general. An integrated team with orthopedic surgeons and skilled geriatricians is in order. And a set of protocols for standard preop evaluation and postop management is mandatory.

Related posts:

Reference:

Does Admission to Medicine or Orthopaedics Impact a Geriatric Hip Patient’s Hospital Length of Stay? J Orthopedic Surg 30(2):95-99, 2016.