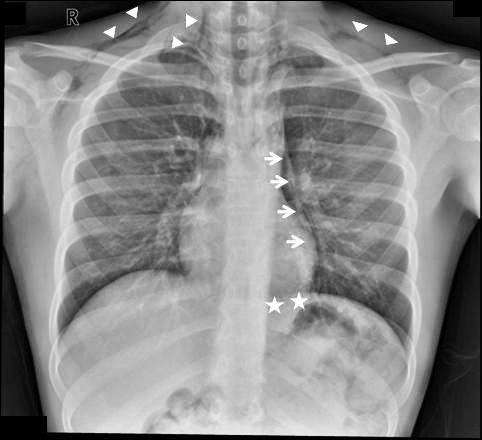

Deer hunting season is upon us again in Minnesota and Wisconsin, so it’s time to plan to do it safely. Although many people think that hunting injuries are mostly accidental gunshot wounds, that is not the case. The most common hunting injury in deer season is a fall from a tree stand.

Tree stands typically allow a hunter to perch 10 to 30 feet above the ground and wait for game to wander by. They are more frequently used in the South and Midwest, usually for deer hunting. A recent study by the Ohio State University Medical Center looked at hunting related injury patterns at two trauma centers.

Half of the patients with hunting-related injuries fell, and 92% of these were tree stand falls. Only 29% were gunshots. And unfortunately, alcohol increases the fall risk, so drink responsibly!

Most newer commercial tree stands are equipped with a safety harness. The problem is that many hunters do not use it. And don’t look for comparative statistics anytime soon. There are no national reporting standards. No matter how experienced you are, always clip in to avoid a nasty fall!

The image on top is a commercial tree stand. The image below is a do-it-yourself tree stand (not recommended). Remember: gravity always wins!