Surgeons and surgical residents rarely see these. And because it’s so uncommon, they frequently don’t recognize the telltale findings on radiographic studies. The TSA runs into the same problem in screening passengers for weapons and other hazards at airports. But it’s the bane of any surgeon’s existence. And it’s a major reason why OR personnel take such great pains to account for everything in the room. It is a catastrophe, and always a preventable one, when some piece of equipment goes missing and ends up left inside a patient.

A number of methods have been developed to try to eliminate this problem. They include careful counts, having someone record anytime anything is placed inside, x-rays, and most recently, RFID tags.

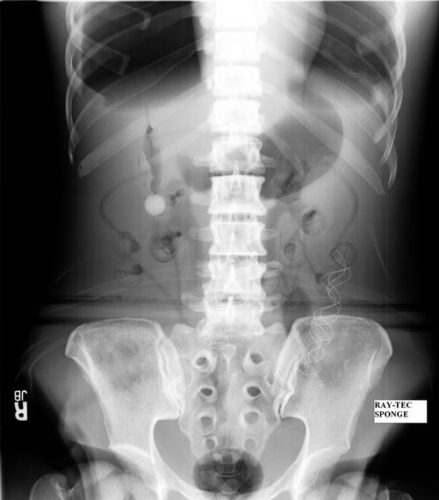

After counting, x-ray is the most common way to try to find missing objects. One would think that these foreign bodies would be easy to see. Metallic instruments are rather easy to spot. But many trauma professionals, even those who work in the OR, have never seen what a positive image of a sponge actually looks like. So here they are. You should never miss one on an xray now.

Surgeons typically use two types of sponges in the OR: Ray-Tec sponges and standard lap pads. Ray-Tecs look like a 4×8 piece of gauze with a mysterious blue string woven throughout it. The string is the only part that shows up on x-ray, and it is very thin and somewhat hard to see. Here are some Ray-Tec sponges outside the body:

And here’s one that was left inside. Note the little squiggle in the left lower quadrant and how easy it is to overlook.

On the other hand, a laparotomy pad is a 4×4 folded cloth pad that unfolds into a larger pad. It has a blue radiopaque tag sewn in the corner, extending along one edge of the pad. Here’s what they look like outside the body:

And here’s one inside a patient. Note the irregular object in the right upper quadrant. Many times the tag is scrunched up and doesn’t look like one.

Bottom line: It’s important for anyone who works in the OR on any body part to be familiar with the appearance of these tags on x-rays. Since it’s generally impossible to get accurate counts before or after a trauma procedure, always image the involved body cavity looking for these telltale signs before closing the patient.

Note: These images were taken from the internet. Patients were not treated at Regions Hospital.