Falls are the most common mechanism of injury at a majority of trauma centers these days. And due to the escalating number of comorbidities in our older population, more and more are taking some kind of anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication. And as all trauma professionals know, falling down and failure to clot do not mix well.

A variety of reversal regimens have been developed, including Vitamin K, plasma or platelet infusion, prothrombin complex concentrate, andexxanet, or idarucizumab depending on the agent. But when it comes to evaluating the efficacy of these agents, there are two important questions that need to be answered:

- Does the regimen reverse or neutralize the offending agent?

and more importantly - Does the regimen have a positive effect, i.e. reduce mortality and/or complications?

This last question has been problematic, especially for the direct oral anticoagulant drugs (DOACs). They are very expensive, but there has been little, if any, evidence that they improve mortality.

A study from the University of Florida at Jacksonville, and sponsored by EAST was performed last year. It was a multi-center, prospective, observational study of data provided by 15 US trauma centers. They collected data on the agents used, reversal attempts, and comorbidities in injured patients taking these drugs, and analyzed for head injury severity and mortality.

Here are the factoids:

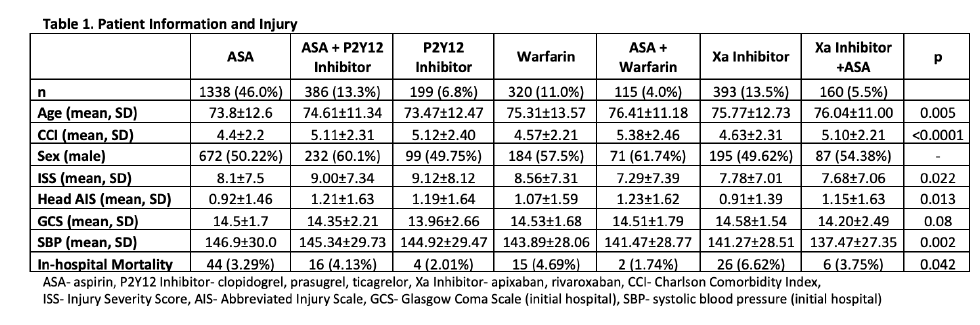

- There were a total of 2913 patients in the study, 46% on aspirin (ASA), 13% taking ASA and a P2Y12 inhibitor (one of the -grels), 11% on warfarin, 4% on ASA + warfarin, 13.5% on a Factor Xa inhibitor, and 6% on a Xa inhibitor + ASA

- Patients on platelet blockers (P2Y12 inhibitor) had the highest mean ISS at 9

- Warfarin was associated with a higher abbreviated injury score (AIS) for head, 1.2

- Controlling for ISS, comorbidities, ISS, and initial SBP, warfarin + ASA had the highest head ISS with an odds ratio of 2.1 (with the lower confidence interval value of 1.19)

- Reversal of antiplatelet therapy with DDAVP was not successful, with no change in mortality (87% with reversal and 93% without)

- Reversal of Xa inhibitors with plasma or PCC was also unsuccessful with a mortality of 100% with reversal and 95% without

The authors concluded that reversal attempts for antiplatelet therapy or Factor Xa inhibitors did not decrease mortality, and shared the observation that combination therapies posed the most risk for severity of head injury.

My comments: Remember, the first thing to do is look at the study group. The authors did not share the inclusion or exclusion criteria for the study in the abstract, so we are a little in the dark here.

The next item that makes this study difficult to interpret (and perform) is the fact that nearly a quarter are on combination therapy for their anticoagulation. So even though nearly 3,000 patients were studied, many of the medication subgroups had only a few hundred subjects. The aspirin group was the largest, with 1,338. This makes me wonder if the overall study had the statistical power to find subtle differences in their outcome measures and support the conclusions.

Now have a look at one of the results tables:

In reviewing the demographic data, the concept of statistical significance vs clinical significance quickly comes to mind. Somehow, age, ISS, head AIS, mortality, and SBP are significantly different between some of the groups. Yet if you examine the specific values across most of the rows, there is little difference (e.g SBP ranges from 137 to 147, ISS from 7-9, mortality from 2-7%). These are all clinically identical. The only row that means much to me is the top one telling how many patients are in a group.

Here are my questions for the authors and presenter:

- Tell us about the study design, especially the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Were there any? How might this have influenced the study group?

- Please comment on your perception of the statistical power of the study, especially with seven groups of patients, each with relatively small numbers.

- Do you have information on the variety of reversal agents used? Were there any standards? Could this have contributed to the mortality in some of the groups?

- Do you have any clinical recommendations based on your findings? If not, what is the next step in examining this group of patients?

My bottom line is that I’m not sure that this study has the power to show us any significant differences. And looking at the information table and logistic regression results (odds ratio confidence intervals close to 1), I’m not really able to learn anything new from it. I’m hoping to learn a lot from the live presentation!

Reference: EAST MCT: comparison of pre-injury antithrombotic use and reversal strategies among severe TBI patients. EAST 2021, Paper 19.