Yesterday, I discussed blood in the urine from a urethra. As I mentioned, there is typically not much from that particular injury. Today, I’ll dig into the three causes of real hematuria.

All of these tubes show gross hematuria except the one on the right.

- Bladder injury. This can occur with either blunt or penetrating injury. The degree of hematuria is variable with stabs or gunshots, but tends to be much darker in blunt injury. This happens because the size of the bladder injury tends to be greater with blunt force. The bladder injury is not necessarily full-thickness with blunt trauma. It may just be some wall contusion and underlying mucosal injury. But frequently, with seat belt injury and/or A-P compression injuries to the pelvis (“open book”), the injury is full thickness.

- Tip: If less than 50cc of very dark urine flow from the catheter upon insertion, it is likely that your patient has an intraperitoneal bladder rupture!

- Ureteral injury. This injury is very rare. The most common mechanism is penetrating, but this structure is so small and deep that it seldom gets hit by naything. Patients with multiple lumbar transverse process fractures will occasionally have a small amount of hematuria, probably from a minor contusion. More often than not, the hematuria is microscopic, so we should never know about it.

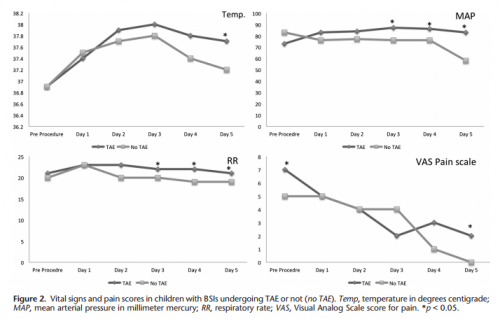

- Kidney injury. The most important fact regarding renal injury is that the degree of injury has no correlation with the amount of hematuria. The most devastating injury, a devascularized kidney, frequently has little if any gross hematuria. And conversely, a very minor contusion can produce very red urine.

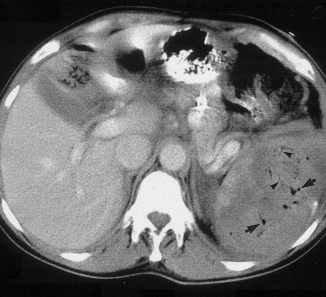

So what about diagnosis? It’s easy! If you see gross hematuria, insert a foley catheter (if not already done) and order a CT of the abdomen/pelvis with contrast, as well as a CT cystogram. The latter must not be done using passive filling of the bladder with a clamped catheter. Contrast must be infused into the bladder under pressure to ensure a bladder injury can be identified.

CT scan is an excellent tool for defining injuries to kidney, ureter, and bladder, and will identify extravasation into specific places and allow grading. Specific management will be the topic of future posts.