The current standard of care is to vaccinate patients after splenectomy to prevent overwhelming post-splenectomy sepsis (OPSS). The real questions are, is this reasonable and is it needed after splenorrhaphy or angioembolization, too?

The spleen was recognized as contributing to infection resistance in the early 1900s. A study on post-splenectomy sepsis that has been widely quoted was published in 1952. Unfortunately, the children involved all had hematologic disorders, so it is difficult to determine if their sepsis deaths were due to splenectomy or their underlying disease.

Reports of sepsis and death continued to accumulate in the latter half of the last century, but there was a tremendous amount of overlap in patient cases. Richardson reviewed the world literature to date and found that, as of about 2003, there were roughly 70 total cases worldwide since the beginning of time, with a death rate of about 30%. Basically, there are more published papers and reports on death from OPSS than there are actual cases!

This flawed data directed a push toward splenorrhaphy and then to nonoperative management of splenic injury. Guidelines have been developed and revised that suggest that the following vaccines should be given to patients with splenectomy:

- Pneumovax 23 – .5cc SQ, booster every 6 years

- Haemophilus B conjugate – .5cc IM, no booster

- Meningococcal vaccine (polysaccharide or diphtheria conjugate) – .5cc (route depends on vaccine), booster status unclear

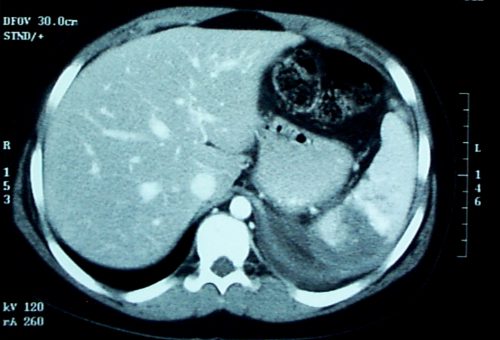

There is no good data at all on vaccine administration after angioembolization. Animal studies suggest that at least 50% of the spleen must be perfused by the splenic artery in order to maintain immune competence. Patients who have CT or angiographic evidence that a significant portion of the spleen is not perfused should probably undergo vaccination.

Given the rarity of OPSS and the even lower probability of dying from it, a definitive study regarding the usefulness of spleen vaccine administration will never be done. So we are stuck with giving them in spleen-injured or spleen-free patients even though the usefulness can never be proven.

Reference: J David Richardson. Managing Liver and Spleen Injuries. J Am Col Surg 200(5):648-669, 2005.