Once the chest is open, the first item of business is to check the heart. In some patients, the inferior pulmonary ligament may prevent you from pushing the lung laterally and superiorly, out of the way. This ligament is a piece of pleura that attaches the lower lobe to the medial diaphragm and mediastinum. Locate it with your fingers and carefully cut it (blindly) with your scissors.

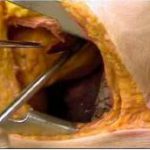

Now look at the heart. What is the rhythm? Put your hands around it. What is the patient’s volume status? If there is the possibility of a penetrating injury, open the pericardium. This structure is tough, and if tamponade is present it will be stretched tight. I find it very difficult to grab the pericardium with forceps and make the initial incision with scissors. Toothed forceps may work, but I just make a very small nick, carefully and directly, with a scalpel. The incision should be placed anterior to the phrenic nerve and vessels, which are usually plainly visible. See the picture on the left, above. The color of the pericardial fluid will immediately indicate whether a cardiac injury is present.

Next, extend the incision (parallel to the bed) to the top and bottom of the ventricle and eviscerate the heart. This will allow careful inspection of all but the atria. If an injury is present, a finger can be used to occlude it until preparations for a repair are made.

Holding the heart is both diagnostic and potentially therapeutic. The “fullness” of this organ is an excellent indicator of the volume status, and if a finger is being used to plug a hole, the temperature of the blood and infused fluids can be determined quickly. All volume resuscitation in this situation should be warmed fluids. And if need be, open cardiac massage is very effective for augmenting circulation.

Related posts:

- Foley catheter used to plug a hole in the heart

- ED thoracotomy practice guideline

- Part 1: Getting In

- Part 2: The Heart

- Part 3: Clamping The Aorta

Image from my personal archive. Not treated at Regions Hospital.