Injured older adults typically sustain those injuries from blunt mechanisms. Radiographic evaluation, particularly CT scans, does not have good supporting literature to dictate which exams should be used in particular patients. There is a long-standing debate on the merits of pan-scan vs. selective scans when using CT.

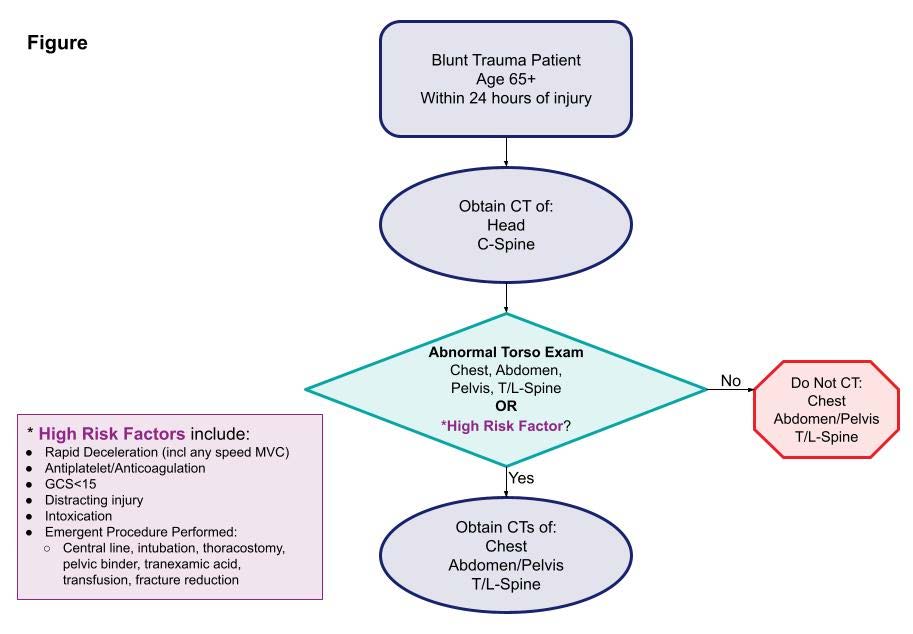

EAST sponsored a multicenter study to look for specific history and physical exam findings that could help direct CT evaluation. Eighteen Level I and II trauma centers participated in a prospective study of patients aged 65 and above. The authors used machine learning to determine clusters of findings that could be used to create decision rules for using a pan-scan vs a tiered scan (head + cervical spine, then possibly torso). The focus was on injuries to the head/cervical spine and the torso. Patients who presented late after injury (24 hours) or died were excluded, leaving 2,587 for study.

Here are the factoids:

- The learning system could not develop a rule for pan-scan usage

- A high-quality model was created to guide the use of selective scanning, which was 94% sensitive with an 86% negative predictive value

- The authors estimated that 12% of patients would be spared a torso scan using the decision tool

The authors concluded that their decision tool has promising sensitivity and negative predictive value and needs further prospective evaluation to validate it.

Bottom line: As our use of machine learning and AI advances, work like this will continue to accelerate. One of the benefits of using AI as a tool is its ability to sift through enormous amounts of raw data to detect faint but significant signals.

The downside is that much of what we record is garbage, making detecting that signal much more difficult. However, the process is inexpensive and can potentially advance health care in a variety of ways.

The presenter and authors should describe the specific machine learning technique used and outline its particular strengths and weaknesses. Expect to see more and more abstracts like this coming down the pike. And when someone starts applying large language models like Chat-GPT to this type of medical data, look out!

Reference: Scanning the aged to minimize missed injury: an EAST multicenter study. EAST 2024, Podium paper #24.