So after two days of pros and cons about helicopter EMS (HEMS), we lead up to this. The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, Emergency Medical System subcommittee, has released a set of guidelines on appropriate use of HEMS. It’s been endorsed by the National Association of EMS Physicians and looks like a lot of thought has gone into it.

Here are the factoids about the HEMS guidelines:

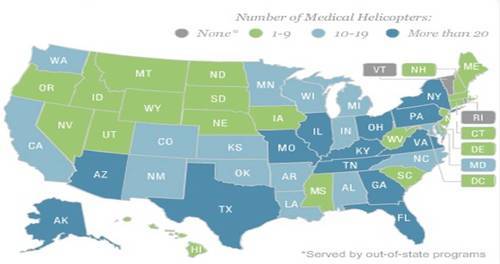

- Must be integrated with your trauma system

- Must utilize standardized field triage guidelines that should be applied consistently throughout your trauma system

- Is blind to the insurance status of the patient

- Uses a regional dispatch system. Self-launch should never happen.

- Referring physician to receiving physician conversations must occur when considering transportation mode (air vs ground) for interfacility transfers

- There must be good online medical direction from a physician

- Offline medical direction must be based on protocols and policies developed by the trauma system

- There must be regular PI review of all HEMS transports to ensure compliance

- HEMS crews must have regular training opportunities

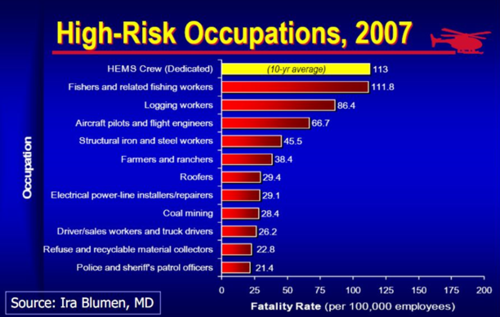

- A culture of safety must be maintained

Bottom line: We absolutely must take a critical look at our patient transport practices and procedures. To ensure even-handed application of best practices, our state trauma systems are going to have to step up and address this issue so the right patient will get to the right hospital at the right time, safely and cost effectively.

Reference: Appropriate use of Helicopter Emergency Medical Services for transport of trauma patients: Guidelines from the Emergency Medical System Subcommittee, Committee on Trauma, American College of Surgeons. J Trauma 75(4):734-741, 2013.