You’ve just been pre-notified of an incoming trauma activation: gunshot to the face. No other information. How concerned should you be? Here are some things to think about as you wait for the patient to arrive:

- Is it really a gunshot? Sometimes shotgun injuries are reported as gunshots. Big difference!

- Will I need to preserve evidence? In general, yes. In most cases other than suicide attempts, there is probably a good chance that criminal activity was involved. Be prepared to preserve all patient belongings in paper bags, and have a chain of custody form available.

- Am I and my team safe? There is a possibility that someone wants your incoming patient dead. They may want to finish the job, in you emergency department. Make sure the area is secure.

Once the patient arrives, it’s best to think through things via the ATLS framework.

- Airway. If the injury involves the lower part of the face or neck, make sure the airway is safe and/or secure. Blood may create problems, as can edema from injury to soft tissues, especially in the floor of the mouth.

- Breathing. Not a problem with these injuries unless significant aspiration has occurred.

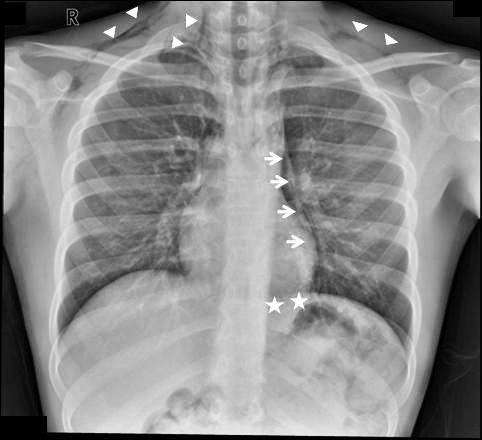

- Circulation. The face can really bleed, and only a few areas are amenable to the usual surgical control (clamping, tying). Direct pressure must be used for the rest, and this doesn’t always work. Bleeding from sinuses may be controlled with packing or the foley catheter trick (inserted through bullet tract). But if you can’t stop it, then it’s time to expedite to the OR.

- Disability. You do have to worry about the cervical spine if the path of the bullet is not obvious. If the patient is stable, immobilize the neck and use the CT scanner to see if any fragments involved the spine. If you must run to the OR with an unstable patient, then try to quickly shoot an old-fashioned cross-table lateral. This will give you quick and dirty info on how much you can manipulate the neck.

Related posts: