Technology: The VeinViewer

I’m always interested in technology that makes what we do easier. Here’s an objective look at an interesting machine that’s been around for a while. It uses near-infrared light to detect skin temperature changes to allow it to map out veins. It then projects an image of the map in real time onto the skin. In theory, this should make IV starts easier (as long as you can keep your head out of the way of the projector).

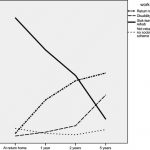

A paper just published from Providence, Rhode Island looked at this device to see if it could simplify IV starts in a tertiary pediatric ED. It was a prospective, randomized sample of 323 children from age 0 to 17 looking at time to IV placement, number of attempts, and pain scores.

Unfortunately, the authors did not find any differences. They found that nearly 80% of IVs were started on the first attempt with or without the VeinViewer, which is less than the literature reported 2-3 attempts. This is most likely due to the level of experience of the nurses in this pediatric ED.

The authors did a planned subgroup analysis of the youngest patients (age 0-2) and found a modest decrease in IV start time (46 seconds) and the nurse’s perception of the child’s pain. Interestingly, the parents did not appreciate a difference in pain between the two groups. This may be due to the VeinViewer’s pretty green display acting as distraction therapy for the child.

Bottom line: This paper points out the importance of carefully reviewing all new (read: expensive at about $20,000 each) technology before blindly implementing it. In this case, an expensive peice of equipment can’t improve upon what an experienced ED nurse can already accomplish.

Reference: VeinViewer-assisted intravenous catheter placement in a pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med, published online, doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01155.x, 2011.

I have no financial interest in Christie Digital Systems, distributor of the VeinViewer Vision®.