Most trauma patients

are considered to be at some risk for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and/or

venous thromboembolism (VTE) during their hospital stay. Trauma professionals

go to great lengths to screen for, prophylax against, and treat these problems.

One of the tougher questions is, how long do we need to worry about it? For

fractures, we know that the risk can persist for months. But what about head

injury?

A group at Brigham

and Women’s Hospital did a large database study looking at the VTE risk in adults

who sustained significant head injury, with only minor injuries to other body

regions. They tried to tease out the risk factors using multivariate regression

models.

Here are the

factoids:

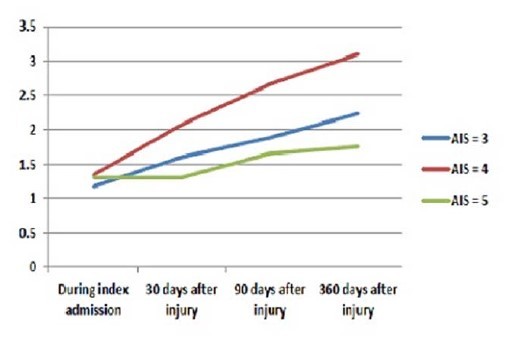

- Patients were only included if their AIS Head

was >3, and all other AIS were <3 - Of the over 50,000 patients in the study,

overall incidence of VTE was 1.3% during the hospital stay, and 2.8% overall

within 1 year of injury - Risk factors for VTE after discharge included

age > 64 (3x), discharge to a skilled nursing facility (3x), and prolonged

hospital length of stay (2x)

Incidence of VTE over time

Bottom line: View this paper as a glimpse of a potential unexpected

issue. The risk of VTE persists for quite some time after head injury (and

probably in most other risky injuries like spine and pelvic fractures. The

three risk factors identified seem to identify a group of more seriously

injured patients who do not return to their baseline soon after injury. We may

need to consider a longer period of screening in select patients, but I believe

further work needs to be done to help figure out exactly who they are.

Reference: How long should we fear? Long-term risk of

venous thromboembolism in patients with traumatic brain injury. EAST 2016 Oral

abstract #28.